Ideology Theater

On Monday, November 12, 2018, several national media in Sweden report that a housing association in Kviberg, Gothenburg has erected a 2.5-meter-high fence (8 feet) to protect the association’s property from their closest neighbors. And the fence is not only high; it also has barbed wire (!):

Housing Association Protects Itself From the Neighbors—with Barbed Wire

Headline in GT (Göteborgs-Tidningen), November 12, 2018.

The fence has in fact already been there for a couple of years, but only recently, just this year, it was graced with several rows of barbed wire along the top, and this completely unique (?) occurrence (for Sweden)—erecting a fence in a residential area with barbed wire no less—lead to a media scramble to report the event.

The chair of the housing association—in which the members all own their apartments—says to GT (Göteborgs-Tidningen) that the residents who live in the neighboring rental apartment buildings are gangsters who destroy,

while the district manager of the public housing company Poseidon, who owns and manages the rental apartment buildings in question, is more diplomatic when he tells GT that the barbed wire creates a feeling of us and them

in the neighborhood, which is sad and unfortunate.

1

Do you remember how you reacted when you first saw the gangsters who destroy

quote in the paper? Was it with indignation? This is absolutely no way to treat one’s fellow human beings.

Or did you think that, well, it’s the goddamn truth, isn’t it? Or were you caught off guard and slightly embarrassed by your own sudden involuntary giggle, feeling guilty for taking such delight in someone fearlessly expressing in public an opinion that everyone knows is politically incorrect?

What political signals do the articles on barbed wire in Kviberg send? What signals do you yourself send when you discuss with your friends whether barbed wire is ok or not ok?

Though originally used mainly by sociologists to describe how one continually sends signals to others within religious organizations and communities—signals regarding one’s piety and one’s virtue, in word and in deed, in the choice of fashion and lifestyle—the concept of

virtue signaling

would eventually come to be associated instead with issues of identity politics and political correctness. In its modern and currently very narrow (and derogatory, pejorative) meaning, virtue signaling refers to a behavior typical of political activists who loudly and aggressively criticize their opponents in public, but without the ambition to actually convince their opponents, since the loud protests in fact are just a way of showing others in one’s own political camp where one stands, and to eagerly send them a signal that one is just as righteous as they are.

But here I intend to use this concept, virtue signaling, in a completely different context, a context in which the term as far as I know has never been used before. I intend to use it to talk about architecture and urban planning, and about the ideals and ideologies that architects and city planners signal when they draw and build. Virtue signaling—or let’s call it

ideology theater

—has, especially in 20th century architecture and urban planning, often been expressed in very dubious metaphors: the wall

oppresses while the void

liberates, a glass facade is transparent and therefore democratic,

etc. Put simply: I-am-a-good-person-if-I-build-a-glass-house-in-a-landscape-without-walls-or-fences (cf. Appendix 1 of 3

below). Architecture and urban planning in Sweden throughout the 20th century is full of similar, hardly objective, and from a sociological standpoint, poorly supported examples of ideology theater—which nevertheless for the individual architect or planner must have had a large pay-off psychologically at the time they were put forward, in the form of accolades and peer recognition, as long as the buildings one designed and the residential areas one planned sent the right kind of signals, signaling altruism, progressiveness and do-goodery.2

But this progressive 20th century architectural ideology theater, characterized by a closed, internal, near-sighted, myopic signaling system exclusively for the members of the architectural profession, meant that ultimately it became fairly unimportant if the buildings built out there in reality really lived up to the metaphorical signals they sent. It became less important if these new buildings really improved the world, or if the people who moved into the new buildings and suburbs really lived freer and happier lives there than they would have if they lived elsewhere.

This of course does not mean that everyone who publicly signals altruism, progressiveness, and do-goodery are always self-serving, short-sighted and myopic—but even when altruism and improving the world are being signaled by individuals with high levels of artistic and intellectual integrity, one should always be on guard:

In a famous poem by American poet Robert Frost (Mending Wall

from 1914—the poem is reproduced in its entirety in Appendix 2 of 3

below), the poem’s protagonist asks his neighbor a modest question: Would it not be best to simply tear down the wall that runs between our properties, a stone wall that gets damaged every winter after the activities of hunters, and which we both need to repair each spring? The neighbor answers with a simple

good fences make good neighbors

and continues repairing without giving it another thought. The neighbor’s laconic reply has over the years become a well-known saying in the English-speaking world—and this despite the fact that the author and the poem’s protagonist seem to think that the very best thing would really be to tear down the wall and not to have to constantly rebuild it. And moreover, not just tearing down this particular wall: one can read between the lines that the author, just like the poem’s protagonist, wishes one could tear down many other walls erected between people—including metaphorical walls.

But I am clearly on the laconic neighbor’s side in this dispute. Walls liberate (now we are talking about physical walls, not the wall-as-metaphor, not about walls

in a figurative, nonliteral sense), walls allow people to live close to each other without disturbing each other unnecessarily. A family’s two teenagers, constantly fighting with each other in the room they have to share, soon become friends again when the parents build a proper wall that divides the room in two. So that they both get their own room, so that they both have access to something very valuable in a civilized society, namely

a room of one’s own

as Virginia Woolf expressed it. The common utopian fantasy of a world without walls and without borders, the fantasy that not only Robert Frost but also many, many others have nourished, and continue to nourish, that fantasy, as is well known by now, always leads to tyranny and oppression—something that all of our collective, hard-won, painful experiences of Marxism, socialism and communism in the 20th century have taught us once and for all, have they not? If they did not have that wall between them, Frost’s protagonist and his laconic neighbor, then there would probably be ever more frequent and ever more escalating fights between them, back and forth across the property line. Tearing down their wall would not improve the world, and the poem’s protagonist and his neighbor would not live freer and happier lives without a wall. Beware therefore, Robert Frost,

be careful what you wish for

because a society completely without walls or fences is hell on earth. After all, life is long and difficult, and life is particularly difficult when there are no fences or walls, when there are no doors you can close, when you are forced to share your life with people you do not sympathize with, and especially if you are forced to share your life with them entirely on their terms rather than on your own—abominable people who, you know, smack their lips when they eat, listen to bad music at high volume, who understand nothing about driving or child-rearing or politics. Jean-Paul Sartre rightly stated

l’enfer, c’est les autres

or, as it is commonly put when his famous aphorism is translated into English, hell is other people. So, the fact that a housing association in Kviberg sets up fences around its own property is in and of itself nothing to be surprised or upset about. With or without barbed wire.

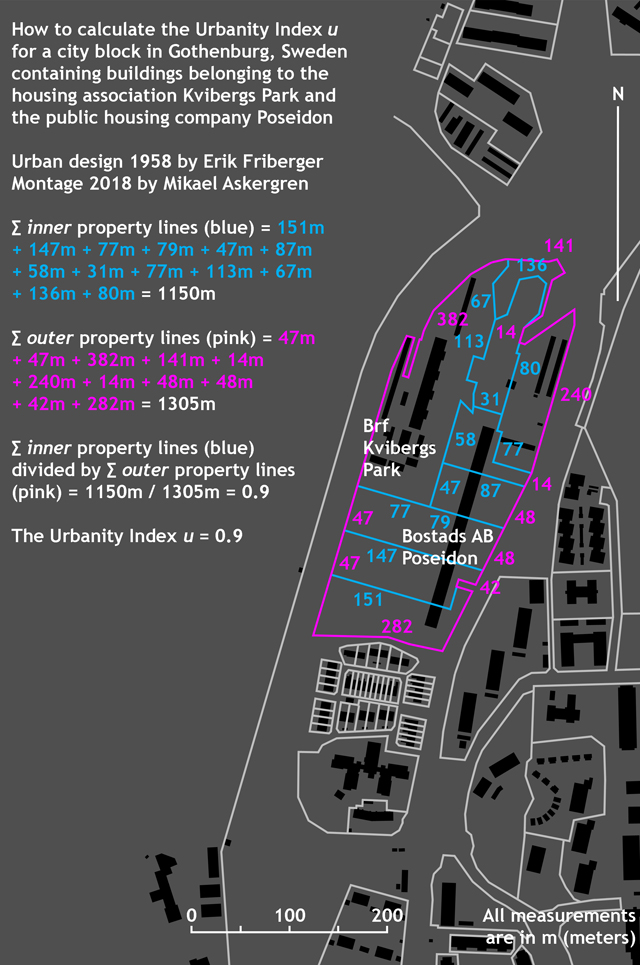

Out of curiosity, I acquired a site plan of the area with all of the block’s property lines drawn in, and calculated the area’s Urbanity Index u. And by my calculation (cf. Appendix 3 of 3

below), our barbed wire block in Kviberg has a very high u-value (u = 0.9)—surprisingly high, because the block was planned and built at a time when nearly all new projects had very low u-values. For such a large-scale residential building complex from the mid twentieth century, one would have expected an almost non-existent Urbanity Index value (u ≈ 0).

But in contrast to what one would normally expect for that era and architectural style, our barbed wire block happens to have a fine mesh of property boundaries—boundaries that divide our 1960s block into as many as nine smaller properties (rather than consisting of one single large property). Which, in turn, made it legally possible for the housing association in Kviberg to put up its barbed wire fence at all, since there has always been a property boundary around the building, a property boundary which of course a housing association is in its full right, legally as well as morally, to erect a fence on.

Which also explains why among all the Swedish suburban neighborhoods of the 1960s, this particular neighborhood, for the very first time in Sweden (?), erects a barbed wire fence towards its neighbors: because there actually exists property lines to build fences on, quite simply. The fact that no barbed wire has appeared in other blocks from the 1960s, in all of those blocks with non-existent Urbanity Index values (u = 0), this fact does not necessarily mean that people living in those blocks necessarily think so much better about their neighbors. (Or are less interested in buying out some of the block’s apartment buildings to form one’s own small housing association.) The value u = 0 in these cases only means that it is simply not legally possible to erect such fences, that property lines have never been drawn in these blocks that would allow new housing associations to form, and to erect fences on whenever they consider that fencing is actually needed.

You may think what you will about barbed wire fences around playgrounds for young children, but in the long run, being able to erect such fences at all in an area with a high u-value offers many advantages over an area with a low u-value. A low u-value allows only one (yes one) future for those who build and live in the only (yes only) property in the block:

Inertia in the real estate economy and lack of diversity in the range of businesses, entertainment venues, and services—but lots of opportunities for ideology theater and virtue signaling amongst architects, planners and politicians.

A high u brings a greater social, cultural and economic dynamism in the city than what a low u does—something I have stated many times over the years, wherever I have investigated the matter.3 A high u-value initially offers a free choice between at least two possible futures for those who build and inhabit a particular neighborhood:

2. (Future 2 of 2 possible futures.) High level of activity in the real estate market and great diversity in the range of businesses, entertainment venues, and services. But, if you prefer, also the illusion of the same kind of future as in a neighborhood with a low u-value.

Yes, in fact, it is possible in a high-u-neighborhood to choose to create the impression of a low-u Future 2

if one so wishes—if one simply chooses to pretend about the property lines that are actually already there, that are actually already drawn in the blocks, if one pretends as if there are no clear boundary lines between yours and mine. One simply refuses to erect fences or walls along the property lines that actually already legally divide the land, and one refuses with equal emphasis to erect fences or walls along the neighborhood’s streets or parks—all in order to at least create the illusion of the kind of legally and economically borderless urban landscape that Robert Frost and other utopians always dreamed of.

Why pretend to live and work in a borderless urban landscape? Why pretend, in a high-u environment? Because the demonstrative lack of visible fences and walls offers comfort, offers for many utopians a welcome and comforting piece of ideology theater. And this of course is preferable to a block with an actual low u. A superficial, cosmetically applied piece of low-u theater is preferable to any attempt to, as a dubious metaphor for a dubious social ideal, actually realize a low u.4

And if you eventually get tired of their pretend game, you can always in a high-u area change your mind. The advantage of a high u is that there is room for changes and shifts in the community’s values over time. If in a high-u area one decides for one reason or another to pursue Future 2

(absolutely no fence), one can at a later stage, in another political or financial situation, quite simply switch to Future 1

(fencing even with barbed wire if that is needed). And then back again! Or vice versa! And all the time with the same structure of subdivided properties, which saves both time and money.

Or (!) run both futures in parallel, simultaneously. Choose Future 1

in one part of the block (cf. Kviberg’s housing association with its now-famous barbed wire fence), and at the same time choose Future 2

in another part of the same block (cf. how Bostads AB Poseidon in our Kviberg example has chosen to voluntarily refrain from erecting fences between the five combined properties they own and manage in the block).

So even if you personally feel more akin to Robert Frost’s utopian protagonist (who dreams of demolished walls) than to his laconic neighbor (good fences make good neighbors

)—and if you consider yourself to be a true altruist, and at the same time rational in your altruism—you should ultimately choose, as an architect and planner, to design and build (and as a citizen, prefer to live and work in) a city with high u-values, because a high u-value not only gives you but also gives your laconic neighbor, gives both of you—despite all of your differences and your different lifestyle choices—a greater freedom to choose your respective futures separately, independently of each other, on your own.

Back then, in the 1960s, when the barbed-wire building in Kviberg first made its appearance, the freestanding volumes in an open landscape, without walls or fencing, signaled of course the right

things. And for the architects who in the 1960s signaled in Kviberg their improve-the-world zeal mainly through this kind of open-landscape-is-democratic metaphor, for them a fence with barbed wire would of course be a shameless provocation. But let us here and now, in our own 2010s, decide to not get caught up in what barbed wire signals, but instead ask ourselves what barbed wire does, what barbed wire actually accomplishes so to speak, what kind of work the barbed wire carries out for the block, from a purely objective, purely practical point of view.

A 2.5-meter-high fence with barbed wire prevents a certain type of undesirable traffic over a certain type of boundary in the city—this is what a fence does. In this way it carries out a type of work that social services, the police, and the justice system would otherwise carry out.

But a fence is not only something that separates people and property. A fence, at the same time, in fact also enables people and things in the city to come closer to each other. Fences, walls, and barriers in the city make it possible for people and businesses that neither can nor want to live or operate with each other (in the same space) to still share space in the city (share it between themselves) and live and work very near each other. Fences, walls, and barriers make it possible to reduce the physical distance between businesses that otherwise, without fences, walls, or barriers, would need to be kept far, far apart. Fences, walls, and barriers make things possible. Fences, walls, and barriers make the city possible.

Appendix 1 of 3. Metaphorics (1995)

Two short essays by Mikael Askergren in the form of encyclopedia entries

for An Encyclopedia of the City, a special urbanity themed issue of the architecture magazine MAMA (Magasin för Modern Arkitektur), Stockholm, no. 10-1995.

Encyclopedia entry METAPHORICS: The Wall

as Metaphor

Power and might is sexy, regardless of the policy it represents. Berlin divided trembled with lust. Two hatefully opposed political systems in Berlin could not take their eyes off of each other and shuddered at each other's touch. With West Berlin, the phallus of the West, rammed into the anus of the Eastern Bloc, Moscow could hardly do anything but insist on safe sex and a condom as protection against political infection and mass emigration. The wall was built. But then again, the only safe sex is no sex.

Walls, closedness, opacity, darkness and mass are in the modernist tradition metaphors of evil. For decades the Berlin Wall was the example par excellence of permanent oppression and cold warfare. While if the Iron Curtain, instead of splitting a European metropolis and cosmopolitan nation, had cut through uninhabited Central European forests and divided Germanic and Slavic tribes, and if contact between the populations of the two economic cultures, and the rulers in Washington and Moscow for that matter, had been reduced to prudish second-hand information via Hollywood films and Pravda, world history most likely would have taken a different course. The foremost characteristics of walls are not permanence and potency. The foremost characteristics of walls are instability and impotence. Sooner or later a wall is pulled down or collapses.

Encyclopedia entry METAPHORICS: The Void

as Metaphor

The trinity of the void, transparency, and the absence of mass (tabula rasa) are in the modernist tradition metaphors for openness, goodness, democracy, for space and society liberated from social hierarchies and class differences, for infinite potential, limited only by the potency and creativity of the heroic subject. The void can be filled with anything, regardless of historical precedent. These metaphorics have also gained a foothold in the establishment, because of how the great physical distances inevitably resulting from creating structural voids seem to have rather the opposite effect: the void and great physical distances serve as a permanent disciplinary factor in existence. While the Bastille and the Berlin Wall can be pulled down once and for all, the distances of Place de la Concorde, Broadacre City, and La Ville Radieuse must be constantly re-conquered; there is a price tag on every crossing and communication. Mobility craves resources. You pay in money, time, labor, planning, and (self-) discipline.

After the first Rodney King trial the largest metropolis of the American west burns. Koreans, who arrived in California long after the Afro-Americans, have already advanced to a higher standing in society and suffer the same aggression as the white people of L.A. The melting pot

does not exist, despite an egalitarian and originally revolutionary constitution. Invisibilities, rather than built walls, separate the classes and races like they always have. Those who have a choice choose to protect themselves, not with walls and barbed wire (which could be pulled down), but by leaving metropolitan L.A. and moving to Phoenix or Santa Fe, by establishing great physical distance from the undesirables. Mobility craves resources.

During a visit to the National Museum of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, I notice one painting. In the painting there are two classical buildings, which are linked by a wall fronting the street. There is a gateway in the wall. The symmetry of the motif as well as of the composition in the painting draws one’s attention away from the buildings and the paved street in the foreground, and instead directs the gaze towards the space beyond the wall and the gateway, to the vanishing point of the perspective, creating an expectation of a spatial climax and a climax of substance. But instead one finds—nothing, a climax of emptiness, transparency, and immateriality.

The painting is by Vilhelm Hammershøi. Its void and its nothingness linger in my memory. In my fantasy, I long to cross the street, pass through the gate, and enter that nothing-at-all. I soon realize that my reaction to the painting has nothing to do with any artistic qualities. My fascination and the suggestiveness of the painting have other origins. I have had a close encounter with the utopian within me.

Appendix 2 of 3. Mending Wall (1914)

Mending Wall

by American poet Robert Frost (1874-1963) was first published in 1914, in the collection of poems North of Boston. The poem is republished below in its entirety.

Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun,

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows?

But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Appendix 3 of 3. On the Urbanity Index u in Kviberg

For a detailed account of how and why one uses the Urbanity Index, see Urbanity: What is it? or How to Calculate the Urbanity Index u (Urbanitet, vad är det? eller Hur man räknar ut urbanitetstalet u

) in the architecture journal Kritik, no. 32-December, 2016, and also the follow-up article Ask for Kenneth (Fråga efter Kenneth

) in Kritik, no. 37-July 2018.

The city block in Kviberg that we have focused on here consists of a total of nine independent properties. The names of the properties are:

Kviberg 22:1

Kviberg 22:6

Kviberg 22:7

Kviberg 22:8

Kviberg 22:9

Kviberg 22:10

Kviberg 22:12

Kviberg 22:55

Kviberg 22:56

The five rental apartment buildings owned by Bostads AB Poseidon were designed in 1958 by architect Erik Friberger to form one single giant building, but in the end it was realized as five separate but connected segments, with each segment constituting its own separate property. (Why this is so, why the block and the architecture in this particular case was divided into segments when the usual practice in the 1960s was to avoid making such divisions, this is something that at the moment I have not been able to determine, and shall return to at a later time.)

Nearby is the freestanding high-rise that belongs to the Riksbyggen housing association Brf Kvibergs Park (Kviberg 22:12), a building designed in 1961 by architect Lennart Green. In contrast to the residents of the neighboring Bostads AB Poseidon property (who all rent their apartments), the residents of the Kvibergs Park housing association all own their apartments.

Three of the properties in the north end of the block (Kviberg 22:1, Kviberg 22:55-Kviberg 22:56) consist mainly of stone outcroppings and a forest of deciduous trees—they have not been developed.

I begin my calculation of the Urbanity Index by calculating the sum of the lengths in meters of the block’s inner

property lines (marked in blue in the adjacent illustration) = 151m + 147m + 77m + 79m + 47m + 87m + 58m + 31m + 77m + 113m + 67m + 136m + 80m = 1150m

Then I calculate the sum of the lengths in meters of the block’s outer

property lines (marked in pink in the illustration) = 47m + 47m + 382m + 141m + 14m + 240m + 14m + 48m + 48m + 42m + 282m = 1305m

The Urbanity Index u of the block is arrived at by dividing the sum of the block’s inner

(blue) property lines by the sum of the block’s outer

(pink) property lines:

∑property linesinner / ∑property linesouter = 1150m / 1305m = 0.9

All u-values above 0.5 may be considered acceptable in cases where a socially, culturally, and economically dynamic development is desired, i.e., a genuine urban development of a neighborhood or district over time. And the higher the u-number, the better: in the urban environments that we all intuitively recognize and appreciate as socially and culturally and economically dynamic, in other words, that are genuinely urban, in those urban areas the u-value is always a little higher than 1.0.

Ideologiteater

Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

The Urbanity Index u

urbanitythan, for example, the floor area ratio FAR. A list of links to all articles in this series:

About the Urbanity Index u

Illustrations

•

Housing Association Protects Itself From the Neighbors—with Barbed Wire(Headline in Göteborgs-Tidningen, November 12, 2018). Read the article in its entirety (in Swedish) on the GT website:

Göteborgs-Tidningen

• Robert Frost, 1913.

creatureandcreator.ca

• Virginia Woolf, 1902.

commons.wikimedia.org

• Jean-Paul Sartre, 1940.

bigthink.com

• Housing association Kvibergs Park. Views from Kortedalavägen.

Eniro Kartor

• Housing association Kvibergs Park. View from above.

Google Maps

• Housing association Kvibergs Park. View with barbed wire fence.

Google Maps

• The Berlin Wall.

d.ibtimes.co.uk

• Painting by Vilhelm Hammershøi:

Asian Company Buildings, Seen from St. Annæ Gade in Christianshavn, Copenhagen(Asiatisk Compagnis bygninger, set fra St. Annæ Gade på Christianshavn, København, 1902), Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

commons.wikimedia.org

• Montage with u-Index calculation (Mikael Askergren, 2018).

Footnotes

Urbanity Index,but the decisive importance of property subdivision for urban development was already clear to me for a long time. Cf.

Berlin: enväldets levande och demokratins döda stad(Berlin: The Living City of Autocracy—The Dead City of Democracy) in the architectural journal Arkitektur, Stockholm, no. 2-2011, and Stadsbyggnad diskuteras (

Urban Planning Discussed) in Arkitektur, no. 5-1992, republished with the title Problemet med bostadsområdet S:t Erik (The Trouble with the St. Erik’s Housing Estate) in the architectural journal Kritik, Stockholm, no. 4/5-March, 2009.

Urbanitet, vad är det? eller Hur man räknar ut urbanitetstalet u) in Kritik, no. 32-December, 2016; and Ask for Kenneth (Fråga efter Kenneth) in Kritik, no. 37-July, 2018.