An Encyclopedia of the City

Texts for An Encyclopedia of the City, a special themed issue of the architecture magazine MAMA (Magasin för Modern Arkitektur), Stockholm, Sweden, no. 10-1995.

The special issue’s Editorial

was written and signed by the Encyclopedia’s three guest editors: Mikael Askergren, Johan Johansson, and Lars Marcus.

What follows are seven short texts, all by Mikael Askergren, all encyclopedia entries

for An Encyclopedia of the City.

Editorial

This issue of MAMA is about the city, not about architecture.

Not least among architects, there is a prevailing conception of the city as an architectural problem, a subdivision of the overarching discipline of architecture. The design of a chair, the design of a building, and the design of a city are viewed as variations of the very same problem, size alone being the only thing which distinguishes furniture design from the construction of buildings, and the construction of buildings from city planning. The architectural and formal properties of the city are thereby focused and elevated into being the point of departure for the building of the city. Thus, the town plan, free from the external demands which used to determine its design, is placed on the level of the house: urban design is reduced to architecture.

Of course, it is tempting for the architect to view all problems from the perspective of architecture. If so, everything may be understood as architecture: novels, dance, pastries. For the architect, this becomes a way of expanding his or her field of work as well as the understanding of his or her vocation. For the author, the choreographer, or the baker, the same reasoning becomes an irritating and undue reduction of the novel, the dance, or the pastry. To view the city as architecture must be understood as a reduction of the city.

However, this outlook is so common that we have come to take it for granted, but it is only one of the theories or ideologies of the city which one may choose as a starting point—or reject. One can choose what shall be planned, one can choose if an architect shall carry out the job, and the architect, in turn, can—if that is the case—choose how to approach the task. In and of itself, building a city has nothing to do with architecture. The city is fundamentally an abstract phenomenon, built out of the legal formation of property lines, economic arrangements, social relations and political conditions; it is not a question of architecture. From the perspective of the city, architecture is temporary, arbitrary, and exchangeable. The city is not architecture.

Agoraphobia

agoraphobia (from the Greek agora, marketplace, and phobos, fear)—a. fear of open spaces. b. here: a tendency with the establishment to evade and shun the public realm.

The better off you are, the less interest you show in solving the problems of everyday life together with other people. You buy your own washing machine so that you will not have to make allowances for others in the communal laundry. You put your children in a private school. If you want to play tennis, you build your own tennis court, and so on. One’s personal interest in an inclusive public urban space, accessible to everyone, is inversely proportional to one’s financial and political power to design and build this urban space.

This agoraphobic tendency is shared by all classes: a union boss has a chauffeur and can choose between mingling with people in the street or not. He is as independent, and when all is said and done, as suspicious of the intractable urban condition as the industrialist.

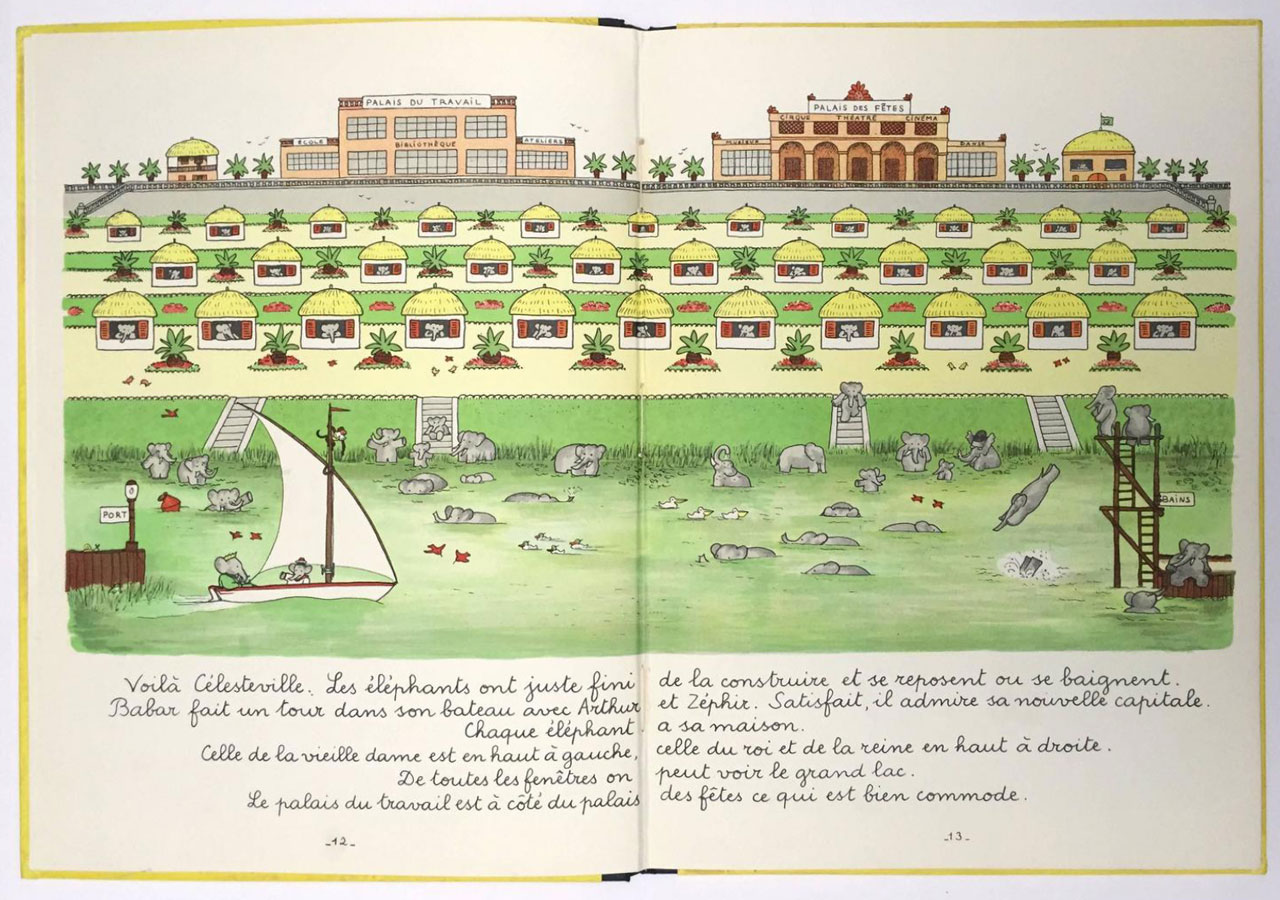

Célesteville

A philanthropic (or rather philelephantic) utopia in the jungle, founded by Babar, the king of the elephants, for his subjects and named after queen Céleste.1 In Célesteville, every elephantine need conceivable to the rulers has been provided for in thoroughly planned and appropriate facilities.

There is a house of labor

and a palace of pleasures,

there are parks, lakes, and recreation grounds. But is Célesteville a city

? Where are the biker elephants? Are there any gay or lesbian elephants in Célesteville? What treatment is accorded the illegal immigrant elephants from India with those ridiculously small ears?

Image of the City

Environments are invisible. Their ground rules, pervasive structure, and overall patterns elude easy perception.

—Marshall McLuhan

I am five or six years old, and my family has just moved into a yellow wooden house with a hedged garden. My brothers and I are strictly forbidden to go outside the gate when playing outdoors on our own. On one occasion, though, the temptation is too strong. I lure my younger brother to go with me and dig tunnels in the gigantic snowbanks alongside the road, banks the size of mountain ranges during the cold winters of the mid-1960s. The reason I remember this occurrence is not because we get caught (we do not get caught), but because after a while I am overcome by remorse, stop the game, and tell my brother that we must go back into the garden, otherwise perhaps mom and dad, when they get back home from work, will see our disobedient play on the television news. I walk around fretting about this for the rest of the day, and I heave a sigh of relief on finding that the television does not bother to report our illicit diversion:

I do not have the capacity to understand the world, but nevertheless create images of the way in which things and apparently disparate occurrences can conceivably be connected. (Why shouldn’t our disobedience be one of the topics discussed on the television news, whose job it is to inform mom and dad about all the important and interesting things that have happened?) I construct a homemade conception of the world, an image which is more palpable and more real than reality.

I do not remember the general destruction, the demolition sites, and the temporary road bridges over the vast craters in the ground where the Brunkeberg ridge and the Klara quarter used to be. I do not remember everything being ugly,

messy,

and out of order.

My recollection of Stockholm in the 1970s is an image: a picture on a poster of a busty prehistoric stone age blonde in a skimpy rat skin bikini. The blonde has a tail about twelve inches long, smooth, and hairless, but with a little tuft at the end. The poster is advertising a film called: When Women Had Tails.

Twenty years later, the recollection proves correct. On an impulse I go to the National Film Institute in Stockholm and find the poster in the archives. The film—apparently some kind of (sex) comedy—turns out to be Italian, made in 1972, the year of my 12th birthday. I even got the title right. The original title is: Quando le donne avevano la coda. The leading blonde is played by Senta Berger.

The city is invisible; a picture, a piece of paper, a poster is more vivid in my memory than the reality, than the city in which the poster is put up. The image is visible, whereas the city is invisible.

My first attempts at drawing houses are a few years earlier than the recollection of the stone age blonde. I draw freestanding rectilinear blocks of housing in an undefined landscape, tower blocks and composite volumes distributed in an indifferent cartesian space. Mind you, I am still living in that yellow wooden house in a hedged garden at the time. I do not know anybody who lives in a flat or apartment, not even in the city. If I ever end up in a public housing suburb resembling what I draw, I experience alienation and dreariness:

Only the image of the architect’s profession and task, only the image of urbanism, of urban planning as a discipline, as it is presented in the few books and journals available on the subject in the local public library, only the buildings and planned suburbs I see depicted are present in my mind’s eye when I myself put pencil to paper in order to create my own images of possible reality.

With our present planning and building regulation, as is often the case in politics, the perception of the world of the innocent child and the opinions of the man in the street

are romanticized. It is only the grassroots,

those who are very palpably affected by a planning proposal by virtue of being tenants or property owners within the area covered by the draft plan, who are deemed to have the right of protest, and consequently carry the full responsibility of revising both the work of the planning administration as well as the decision making of the politicians. As a result, the viewpoints expressed at public hearings or in appeal proceedings can, without exception (and rightly so, as a visit to any public hearing will confirm) be dismissed as instinctive, and categorically resistant to change, and a manifestation of the NIMBY (NotInMyBackYard) effect. In this way, planners and politicians are spared having to concern themselves with any other image of the city and reality than their own.

Is it Sergels torg or is it an image that Stockholmers, laymen as well as architects and planners, find appalling and feel a desire to improve

?

The no. 9-1994 issue of MAMA magazine has a cover which—unusually for an architectural journal—has received much attention in the media. The picture has been reproduced by both the big national dailies and one of the national evening papers. It is an arranged picture showing Sergels torg invaded by Donald Ducks. Among other things, the article that the picture illustrates discusses Imagineering.

Why of all the articles published in the magazine over the years has this one aroused so much attention and become so widespread? Because of the cover; because of an image, naturally.

Metaphorics

Power and might is sexy, regardless of the policies they represent. Berlin divided trembled with lust. Two hatefully opposed political systems in Berlin could not take their eyes off each other and shuddered at each other’s touch. With West Berlin, the phallus of the West, rammed into the anus of the Eastern Bloc, Moscow could hardly do anything but insist on safe sex and a condom as protection against political infection and mass emigration. The wall was built. But then again, the only safe sex is no sex.

Walls, closedness, opacity, darkness, and mass are in the modernist tradition metaphors of evil. For decades the Berlin Wall was the example par excellence of permanent oppression and cold warfare. While if the Iron Curtain, instead of splitting a European metropolis and cosmopolitan nation, had cut through uninhabited Central European forests and divided Germanic and Slavic tribes, and if contact between the populations of the two economic cultures, and the rulers in Washington and Moscow for that matter, had been reduced to prudish second-hand information via Hollywood films and Pravda, world history most likely would have taken a different course. The foremost characteristics of walls are not permanence and potency. The foremost characteristics of walls are instability and impotence. Sooner or later a wall is pulled down or collapses.

The trinity of the void, transparency, and the absence of mass (tabula rasa) are in the modernist tradition metaphors for openness, goodness, democracy, for space and society liberated from social hierarchies and class differences, for infinite potential, limited only by the potency and creativity of the heroic subject. The void can be filled with anything, regardless of historical precedent. These metaphorics have also gained a foothold in the establishment, because of how the great physical distances inevitably resulting from creating structural voids seem to have rather the opposite effect: the void and great physical distances serve as a permanent disciplinary factor in existence. While the Bastille and the Berlin Wall can be pulled down once and for all, the distances of Place de la Concorde, Broadacre City, and La Ville Radieuse must be constantly re-conquered; there is a price tag on every crossing and communication. Mobility craves resources. You pay in money, time, labor, planning, and (self-) discipline.

After the first Rodney King trial the largest metropolis of the American west burns. Koreans, who arrived in California long after the Afro-Americans, have already advanced to a higher standing in society and suffer the same aggression as the white people of L.A. The melting pot

does not exist, despite an egalitarian and originally revolutionary constitution. Invisibilities, rather than built walls, separate the classes and races like they always have. Those who have a choice choose to protect themselves, not with walls and barbed wire (which could be pulled down), but by leaving metropolitan L.A. and moving to Phoenix or Santa Fe, by establishing great physical distance from the undesirables. Mobility craves resources.

During a visit to the National Museum of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, I notice one painting. In the painting there are two classical buildings, which are linked by a wall fronting the street. There is a gateway in the wall. The symmetry of the motif as well as of the composition in the painting draws one’s attention away from the buildings and the paved street in the foreground, and instead directs the gaze towards the space beyond the wall and the gateway, to the vanishing point of the perspective, creating an expectation of a spatial climax and a climax of substance. But instead one finds—nothing, a climax of emptiness, transparency, and immateriality.

The painting is by Vilhelm Hammershøi. Its void and its nothingness linger in my memory. In my fantasy, I long to cross the street, pass through the gate, and enter that nothing-at-all. I soon realize that my reaction to the painting has nothing to do with any artistic qualities. My fascination and the suggestiveness of the painting have other origins. I have had a close encounter with the utopian within me.

Monstrosity

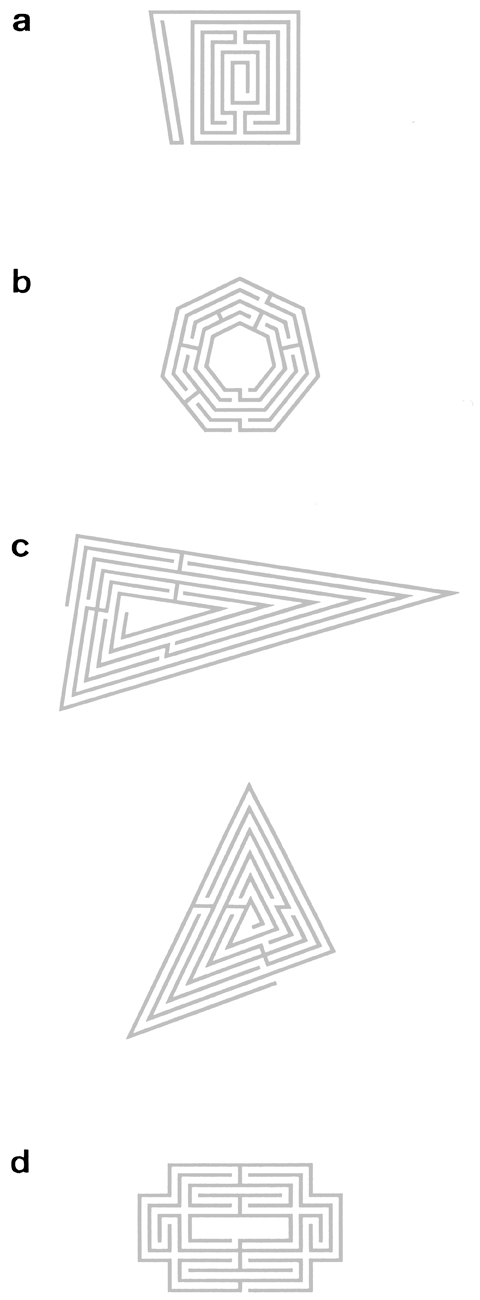

The Minotaur, meandering in its prison, in a labyrinth so ingeniously constructed that nobody could escape it unaided, is thinking: I am the freest of all beings.

Blithely the beast roams through the twists and turns of the labyrinth. Movement, mobility, and communication are strong metaphors for freedom. One may ask whether the Minotaur is aware that the labyrinth is a closed system and that there is a world outside its walls, but this is hardly a question that occupies him. Sooner or later he always bumps into something—or someone—to eat.

The Minotaur is a monster, the fruit of the queen’s lust and her union with a bull—at least according to the king, who will not recognize a monster as his own son. Wherein does the monstrosity of the Minotaur lie? Not in hooves, fur, or horns. His obvious lack of interest in asserting any kind of humanity, together with his blindness to and unwillingness to meekly acknowledge the inferiority imputed to him, all make him a beast.

The labyrinth is so cunningly designed that it is possible to calculate in advance almost exactly which way the beast will choose to go. The labyrinth has no blind alleys. All corridors are interconnected. Every choice of path inevitably leads to a new situation of choice with nothing but ready-made options, where all the consequences are predictable.

Within its lifetime, the likelihood of the beast to choose the correct way out of the labyrinth on enough consecutive occasions is negligible. The exit can therefore be left unguarded, and one can argue, with good reason, that the beast remains in the labyrinth of its own volition.

This choice on the part of the beast to remain in its prison is crucial; the Minotaur is at least semi-human, and his blood ties with the crown make it ethically, emotionally, and politically unfeasible in a rule-of-law nation to detain or dispose of him.

In the myth, it is the ingenious artist, engineer, and architect Daidalos—the Romans called him Daedalus—who constructs the labyrinth at the queen’s command, thereby solving the delicate problem of detaining the beast in a manner acceptable to the empathetic mother and the spiteful father, as well as to the sense of justice in society. The labyrinth of Daidalos is nothing less than the triumph of instrumental philanthropy.

The labyrinth is so cunningly constructed that the Minotaur is held captive not by walls—the metaphor of imprisonment and oppression—but by great physical distances in an infinite void—the metaphor of light, liberty, and change: living and searching for food in the labyrinth is both energy- and time-consuming. Every day the beast covers considerable distances. When he gets his reward in the form of something—or someone—to eat, he has already paid for it dearly with his time and energy. The next reward will be just as far off and will require just as much of him and prove an equally long and arduous journey. The minotaur is a nomadic commuter in constant motion, living in an imploded infinity and peripherality within the labyrinth.

In romanticized depictions of the bustle and diversity of the city, of its emancipatory anonymity and vastness, of its wealth of destinies and secrets, the labyrinth and the labyrinthine are too readily used as concise metaphors of these desirable culture-creating qualities of the urban condition. The labyrinth of Daidalos is a monster, however, just as much as the beast that it imprisons.

Plutocracy

Until 1921, only taxpayers have the right to vote in the Stockholm city council elections. Only very large incomes and accumulations of wealth are taxed, which reduces the electoral body to around one percent of the population. But all taxpayers can vote, even women and private companies, and most voters have more than one vote: in 1863 only 1,900 people and companies vote, but the total number of votes is 145,000.2 The city is a plutocracy resembling the stock-issuing companies of our time in which influence is proportional to how much stock you own. Thus, it lies in the interest of those who hold stock

in the city that information about wealth and finances is made public. The more well off you can show that you are, the more power you have in the public arena of city politics.

The Swedish peerage catalogue is a surviving expression of this former transparency

of the wealthy and powerful. It is a public listing of all members of the Swedish house of nobles, including their interrelations, dates of marriages, birthdates of children, university degrees, etc. The catalogue is complete and perfectly indiscreet. No exceptions or concessions to discretion are made.3

But the public realm in a plutocratic society is the concern of the haves

only. The have-nots

are excluded from power and the public realm, they are not admitted into the shareholders meeting.

Learning from revolutions and social unrest in both America and Europe, concessions are made in the Western world to admit the masses into public space and political arenas. Universal suffrage is introduced. But while the masses immigrate into the public realm, urbanizing it so to speak, the establishment chooses to emigrate. No longer does it lie in its interest to publicly disclose assets that in an egalitarian system do not give political power in proportion to these assets. By divorcing the public realm from power, the marriage of the public realm and the lower classes becomes possible.

Stockholm

By international standards, the Swedish parliament and the Swedish government have a very high representation of women (41.3 and 50.0 percent respectively). If women’s representation in politics is only that which men deliberately abstain from, on account of low prestige and little real influence over their own lives and those of others, the high representation of women in Swedish politics implies that reality is occurring somewhere else, that real social prestige is to be found elsewhere.

Stockholm’s director of the city planning department Ulrika Francke, its vice mayor of city planning Monica Andersson, and its vice mayor of real estate and traffic Annika Billström are all women.4 A majority of the city planning committee’s permanent members are women. The journalists writing in Stockholm newspapers about architecture and urban development are women.

Men are builders. Men want tools for Christmas. Men climb ladders to repair leaking gutters and roofs. Construction workers, electricians, painters, and carpenters are men. If it is true that the act and passion of building is predominantly the concern of men, then the high percentage of women in positions to build and administer the physical public urban space—together with the fact that none of the females Andersson, Billström or Francke has a degree in architecture or civil engineering—implies that in the city of Stockholm in our time, neither the act of building nor the public space of the city is a prominent forum for the expression of power and contemporary culture.

The genuine

city-dweller is puzzled by the festival and asks what the point is to eat food which is admittedly cooked by famous Stockholm restaurateurs but is served on paper plates and eaten sitting on uncomfortable benches, when the food is the same as is served in each restaurateur’s real

restaurant—restaurants, moreover, which are there all year-round. What is the point of hot dogs that are the same as at any hot dog stand but more expensive? What is the point of expensive, uninteresting t-shirts? The festival offers nothing that is not otherwise found somewhere else or at a different time of year. The so-called Stockholm Water Prize is an artificial way for the entrepreneurs of the event (the festival is a private initiative, operated as a business) to try to achieve something specific to the place and occasion. Stockholmers flee the city physically or mentally those days in August when the festival, with its stalls and its trumpery, invades and occupies large parts of the historic city center. But the festival is a big crowd-puller (3.7 million visits by 1.3 million people during the 10 days of the festival in the summer of 1994).5 It is neither absurd nor irrational. Of course, the festival has a point:

In society, the city, like religion and art, has lost the initiative. New Jersey, so greatly despised by the denizens of Manhattan, is today a bigger locomotive of the national economy than Manhattan and Wall Street on the other side of the Hudson River.6 Malmö, Sweden’s third largest city, is no more than a center for regional services according to the 1989 state commission on the future of metropolises in Sweden, just like any other one-horse town, and no longer of any specific national interest. In other words, the nation would hardly notice should Malmöers and their city drift away overnight and sink into the ocean. The same fate is in store for Göteborg, Sweden’s second largest city, if the Volvo automobile industry were to move elsewhere.7 And Stockholm—how much fun is Stockholm? How much fun is Old Town, a monocultural enclave with no food stores but heaps of hand-thrown pots sold by innumerable predictable pottery stores. How much fun is Drottninggatan? How much fun would the Södra Klara district have been today if it had never been torn down and developed

after the war? How much fun are the plans for Sergels torg, Hammarby sjöstad, or the St. Erik’s Housing Estate? For the great mass of the people scattered on the periphery and banished from the drawing rooms and committee rooms of the city, the traditional city really has only one interesting

phenomenon to offer, namely a lot of people:

The inhabitants and dwellers of the city tend to prefer that which is time- and space- and cost-efficient to that which is natural.

During the 1980s we could see young urban professionals pay any amount of money for descending three times a week into a windowless basement to work out. Illuminated trails and recreation facilities in parks and walking areas are certainly free of charge, but a better recreation result can be obtained more rapidly with machinery, which can just as well be in a basement somewhere and often is. The gym is compact and efficient. The outdoor jogging run along space- and maintenance-demanding illuminated trails and green areas, entirely dependent as it is on unreliable self-discipline, takes second place to rationality and technology. People instead go hiking in the mountains for one week of the year: a more time- and experience-efficient form of outdoor activity than the occasional blackbirds and hares encountered on the illuminated trail. To the great masses, by analogy, the Stockholm Water Festival, limited as it is in both time and space, is naturally ideal as an intensive, time-efficient way to meet a lot of people (presumably the festival participant is a sexual being and the festival crowds are experienced as sexy

: the more people, the sexier). Visiting the Stockholm Water Festival is just as intensive an experience of frequenting a city as the mountain holiday is intensive and timesaving for the mountain backpacker.

The Stockholm Water Festival is more interesting to the great mass of people than the real

city and the real

citizens. The genuine

city today is, at most, a means of enjoyment and amusement, just like religion and art, for a set of fans and groupies, as well as for a certain stratum of its inhabitants who have access to the social life of drawing rooms and high society. The city dwellers are neither sufficiently numerous nor sufficiently productive to feed the nation, but they are numerous enough to offer the productive part of the nation a festival that serves as the prototype of a future, post-metropolitan Stockholm.

It is within the discipline of the publicity stunt and the marketing ploy (Sw. jippo

) that one finds ways in which an agoraphobic

establishment8 can address the crisis of the city and urban life. Stunts and ploys address this crisis much more effectively than any attempts at envisaging the street of the future,

9 or pursuing any antiquarian efforts:

When dusk falls, there rises out of the sea a phantom city of lights against the sky. A myriad of embers twinkle in the darkness. A golden spider’s net in the sky.

—Maxim Gorky visiting Coney Island in 1903, quoted by Andreas Theve inConey Island Cyclone,A1 Magazine, Stockholm, no. 2-1992.

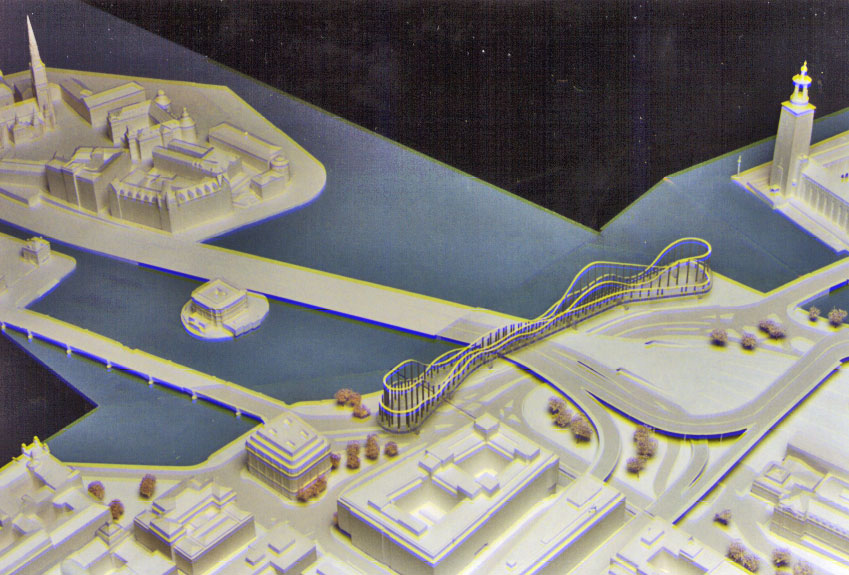

Tegelbacken, together with the Södra Klara district in Stockholm, seen as stony canyons and moonscapes, have substantial picturesque qualities10 in the ghost town genre and are the congenial setting for the post-metropolitan city festival’s cathedral-like main event and trash-queen Jippo Maximus, a roller coaster of the extended, majestic out-’n’-back

kind, solemnly distanced and detached from every context (spatial, functional, or social).

It surpasses everything in the way of amusement with its hyper-efficient technology of sensory excitement: the roller coaster has capsule-like covered cars in which the experience of ups and downs is reinforced with the aid of sound and strobe effects coordinated with the motion of the capsule. The capsule is soundproof and has no windows. Inside the capsule you neither see nor hear anything of the surrounding city. No one in the city sees the passengers inside the capsule or hears their cries.

Editorialof the three guest editors (Askergren, Johansson, and Marcus). Eight texts in total. English translation of all eight texts by Michael Perlmutter.

En stadens encyklopedi

Listen to the audio book with a recording of Mikael Askergren’s texts for the encyclopedia:

Thinking Out Loud #1 (Audio Book in Swedish and English)

More by Mikael Askergren on the Jippo Maximus roller coaster project:

Berg-och-dalbana på Tegelbacken

Illustrations

• When Women Had Tails (Quando le donne avevano la coda), Italy (1970, Sweden 1972). Authentic movie poster in Swedish belonging to Mikael Askergren.

• The Berlin Wall. d.ibtimes.co.uk

• Wilhelm Hammershøi: Asiatisk Compagnis bygninger, set fra St. Annæ Gade på Christianshavn, København (1902). Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark. Wikimedia Commons

• Apropos the famous labyrinth at Knossos: a series of proposals by Mikael Askergren (1992) for a hedge maze/garden labyrinth in the gardens surrounding Medevi brunn, Östergötland, Sweden.

Blast from the Past: Labyrinths and Mazes

• Roller coaster at Tegelbacken, Stockholm, Sweden. Mikael Askergren and Andreas Theve (1995).

Footnotes

Malmö,in which Henrik Häggström summarizes the findings of Storstadsutredningen, a 1989 official Swedish government report on the future for Sweden’s major cities (SOU 1989: 69).

Agoraphobia.

Picturesque.