Horror Limitis

What is it with architects and property lines? Property lines are a part of the city’s economic and juridical realities, but architects avoid them like the plague, and have an almost phobic relation to them.

Let us give it a name, this property-line phobia that all architects and planners suffer from, and call it horror limitis (cf. the Latin horror, fear,

and limes, boundary

). And let us in the following examples explore what significance this horror limitis has had on urban development throughout history.

Strandvägen

Look here. This large grand building is located on Strandvägen, Stockholm’s most exclusive boulevard, next to the Royal National Theater (Dramaten). A powerful art nouveau baroque palace that fills the entire Bodarne city block.1

Or wait a minute. Is this really one palace, is this really one building?

Take another look. Notice how the plaster facade shifts in color. The palace

in fact consists of three independent properties.

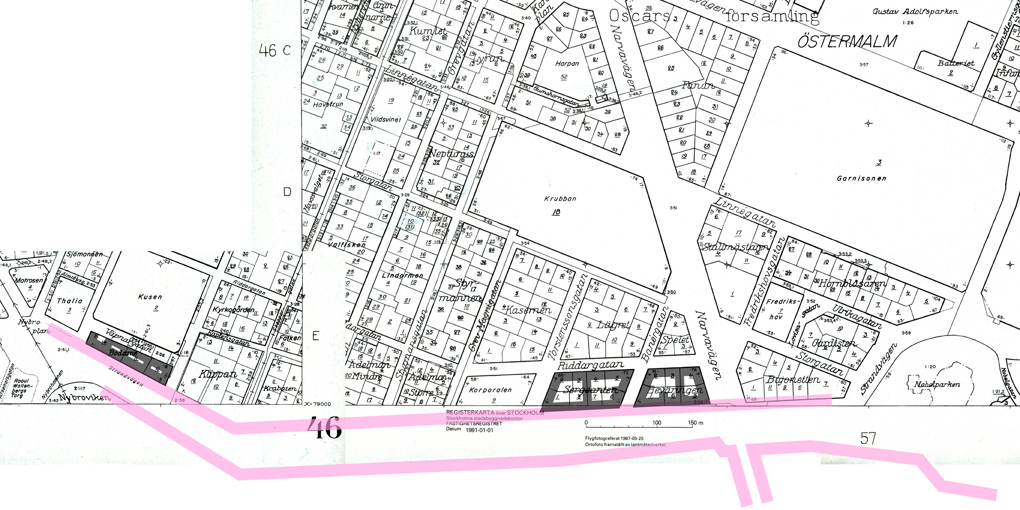

And look here, a bit further away, also on Strandvägen. Notice the shifts in the color tones, notice how the roof landscape has been maintained in different ways over the years. This side of the Sergeanten city block, which faces Strandvägen and the water, is divided into four properties.

And, finally, the adjacent Beväringen block is divided into three economically and juridically independent properties.

The architects that designed the buildings and composed the unified facades in the Bodarne, Sergeanten, and Beväringen blocks along Strandvägen certainly did their best to camouflage the property boundaries (horror limitis). But over time the property divisions have become possible to discern with the naked eye.

Which doesn’t necessarily need to be regarded as a beauty flaw. On the contrary, Strandvägen—despite its large-scale pretentions—has come to be perceived as a unified urban

environment that continually changes over time. Here and there, from time to time. An urban environment that lives.

Gärdet

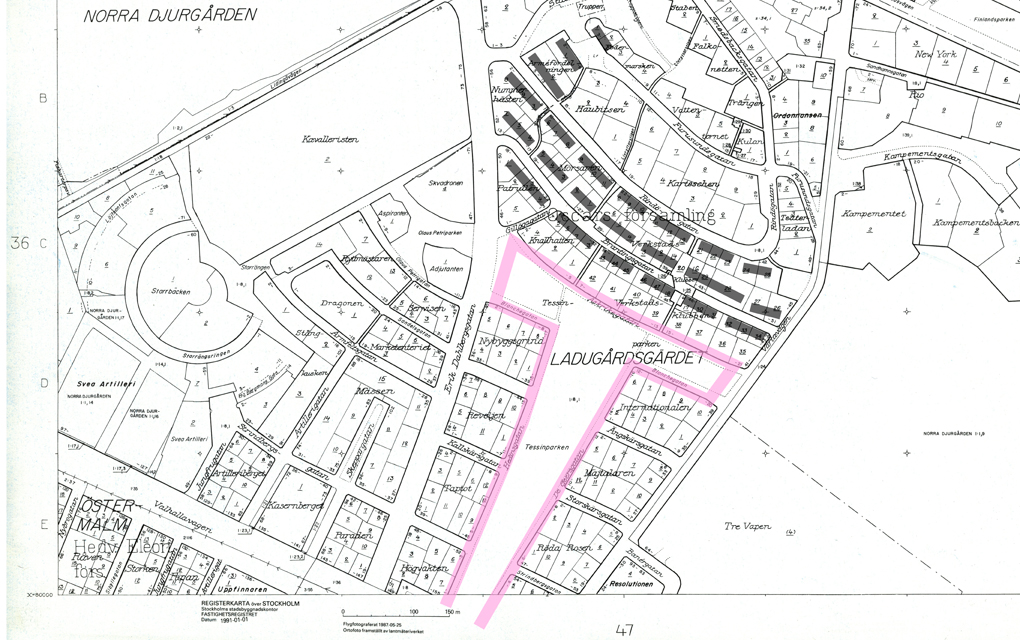

Now on to Gärdet. Look here. At Gärdet there was no desire to build like on Strandvägen, at Gärdet the desire was to build separate buildings-in-a-park instead.

But believe it or not, the blocks and the building plots are just as big at Gärdet as they are along Strandvägen. On the cadastral map of Stockholm—a map that consists only of property lines, a map with no buildings drawn in—the city plan for the green and airy Gärdet area looks exactly (!) like the dense urban environment along Strandvägen.

The narrow blocks of flats along Brantingsgatan and Rindögatan that climb up the slope in slight arcs are divided into economically and juridically separate plots and ownership units in the very same way as the buildings along Strandvägen are.

Gärdet’s park landscape is in fact not a park, it is divided into a plethora of very small plots. The planners have certainly done their best to create the look of a completely pure and unified buildings-in-a-park area. For example, all the blocks of flats along Brantingsgatan and Rindögatan are equally long and wide and high: an expression of the planners’ ambition to create a singular, unified aesthetic for the entire area (horror limitis, again). But the subdivisions into smaller properties, which was typical of the era, has—because of the openness of the landscape—been impossible to camouflage. The subdivision of the park

into smaller plots has always been readable with the naked eye. Most of the property owners at Gärdet have in one way or another marked the boundaries of their own plots: like with a hedge for example.

Which need not be regarded as a beauty flaw. On the contrary, Gärdet, just like Strandvägen, has come to be perceived as a unified, urban

environment. Not the same everywhere.

An urban environment that lives.

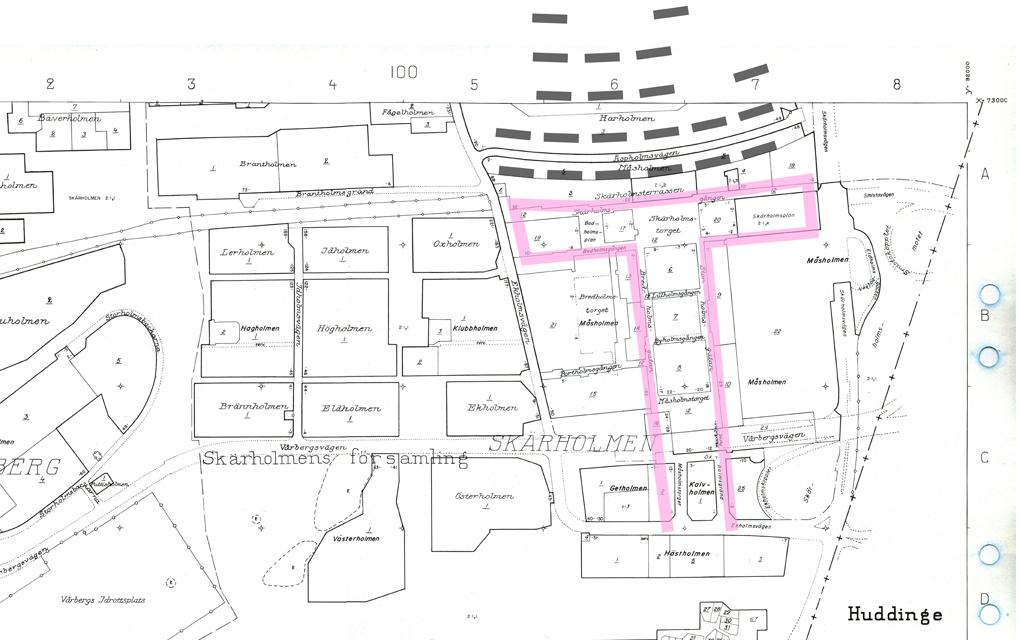

Skärholmen

Now on to Skärholmen. With time, reality, economics, law, and politics caught up with the property-line phobia of architects. Architects and planners no longer needed to engage in wishful thinking, they no longer needed to pretend.

When Skärholmen was designed, there was no longer a need to camouflage some of the property lines, because property lines no longer existed for architects and planners to be bothered by. Property lines had been rationalized away.

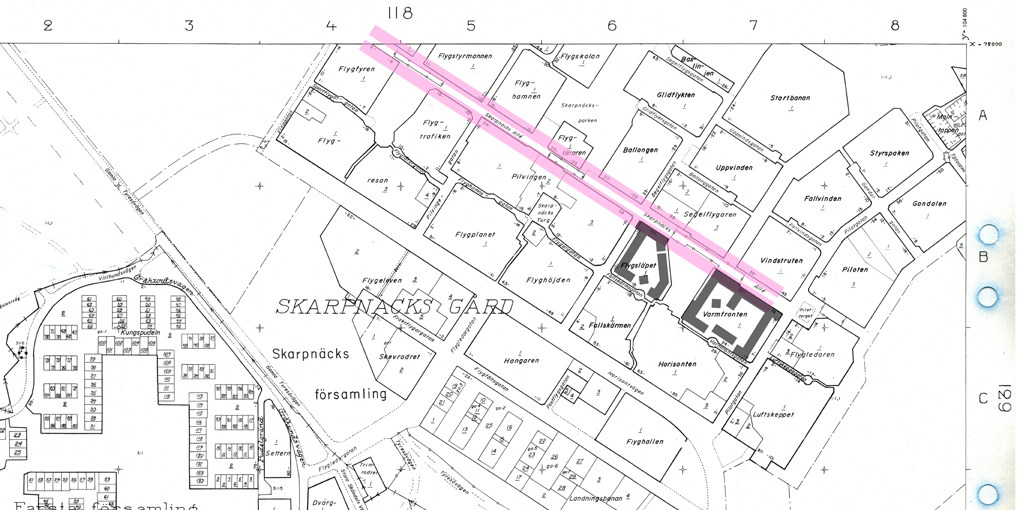

Just like at Gärdet, the desire was to build independent buildings-in-a-park. And the way the narrow blocks of flats along Äspholmsvägen and Ekholmsvägen in Skärholmen climb up the slope in slight arcs also has striking similarities with the situation at Gärdet.

But it would be wrong to conclude that the intention in Skärholmen was to create a new Gärdet

—despite the similarities in the layout. On the contrary, already at Gärdet the desire was to create a Skärholmen

so to speak, if it had only been possible.

But the economically necessary division of land into several different plots and several different building projects made a pure and completely unified buildings-in-a-park development impossible at Gärdet. Gärdet became in the end only

an incomplete prototype for what would later appear—for what would later be fully realized—in Skärholmen.

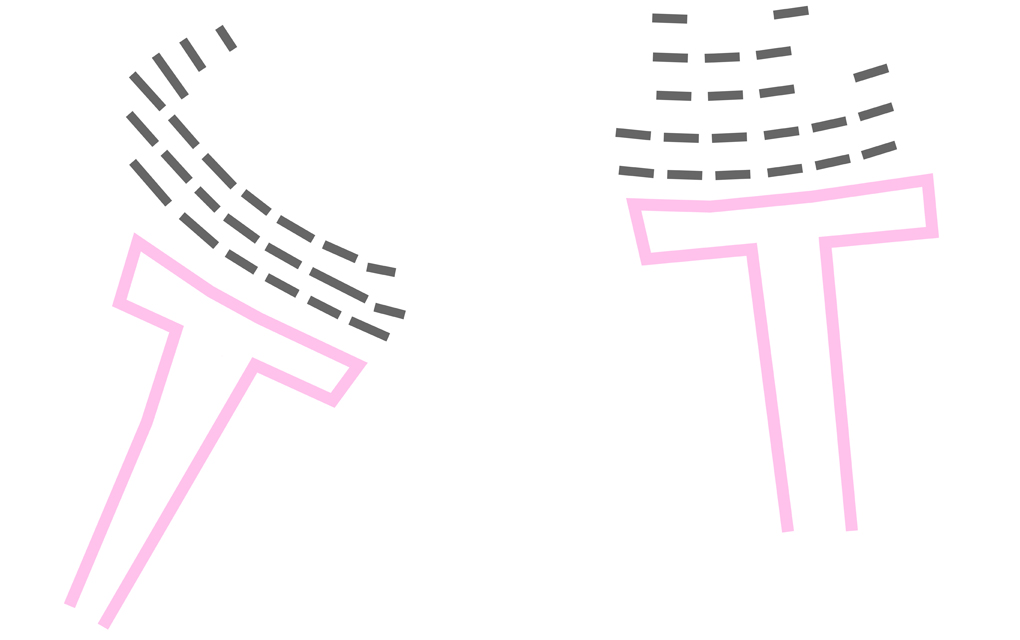

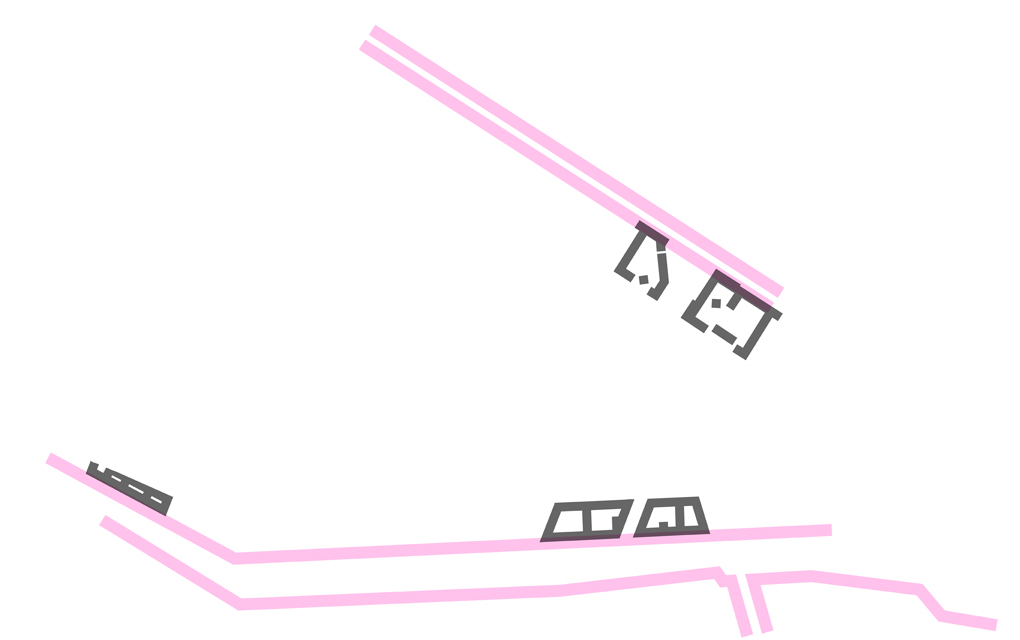

Look here. Below I have illustrated the buildings at Gärdet and Skärholmen as so-called Nolli maps—in other words, a map that only shows the difference between the built and the unbuilt, between building forms and empty space, shown without property lines drawn in.

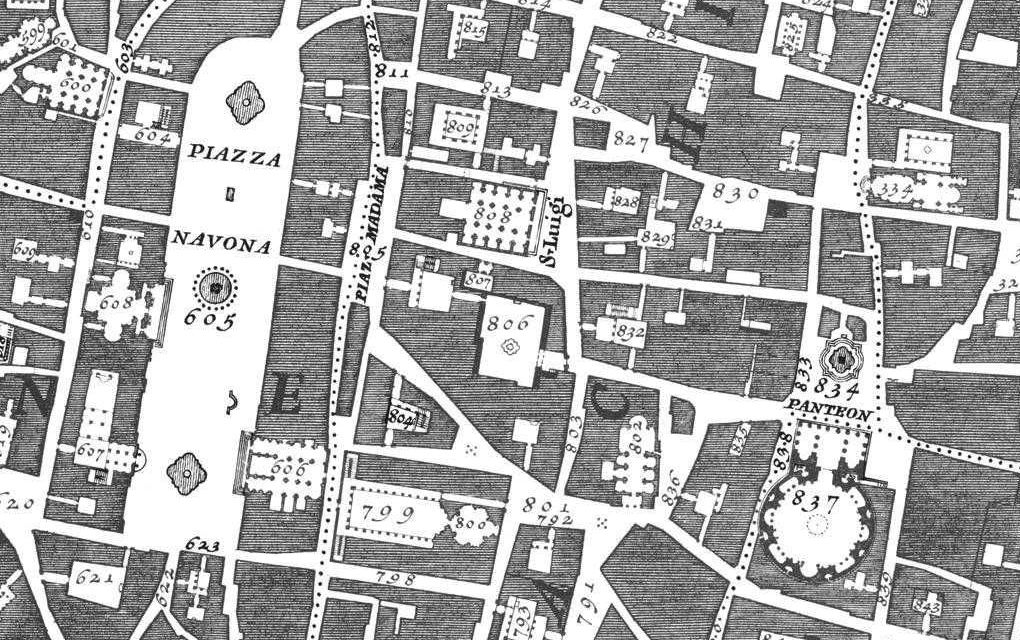

The term Nolli map has its origins in the Nuova Topografia de Roma (1748) map by Giambattista Nolli. His famous map is undeniably very beautiful—but it offers absolutely no information about the subdivision of the built land into independent properties.

It is incidentally probably for this reason that this map is so loved by architects. Nolli did not care at all about showing the divisions of properties in the city—it is as if he did not wish to pretend that in the city of Rome there even existed a subdivision of blocks into smaller plots.

In this way he chose to represent a city in a manner that best corresponded to how architects prefer to think about cities and urban building—namely not at all as juridical and economic abstractions, not at all as a system of boundaries between owner interests, between, in principle, completely independent properties. Instead, the city is only represented in the form of what one can actually see and touch, as a homogenous building mass, a gigantic Barbapapa of stone and glass, without subdivision, without plot boundaries, without property formation.

Nolli’s way of deciding what the city of Rome is

and is not

has appealed to architects much more than, say, a cadastral map...

Be that as it may. Anyone who studies a Nolli map of Stockholm sees immediately that Skärholmen and Gärdet are not only exactly the same in size. Their layouts—compositions with narrow blocks of flats climbing up a hill—are also exactly the same (!). The only (!) actual difference between these building developments is thus the division of properties and the size of the plots: the cadastral map of Stockholm—the map with only property lines drawn in and showing no buildings whatsoever—reveals that the properties in Skärholmen are considerably larger than those in Gärdet.

Which means that no plot boundaries or firewalls break up the buildings in Skärholmen into smaller bits that age and change at a different pace. Which in turn means that Skärholmen is perceived as a deader

environment that Gärdet.

Skarpnäck

Now on to Skarpnäck. It does not take long before a strong and widespread reaction arises against the lack of variety, monotony, and deadness

of the built environment that Skärholmen typifies. Planners and architects respond by making an about-face and begin to build a completely new type of housing area, perhaps with old Strandvägen as a source of inspiration. One no longer creates buildings-in-a-park. Skarpnäck, for example.

Notice that the properties in Skarpnäck, however, are the same size as they are in Skärholmen. In this respect nothing has changed, despite their very different appearance. Architects and planners still abhor an all too fine-meshed net of property lines. Or—which has perhaps become more common with time—do not care about, do not realize (do not want to realize) the importance of property formation and plot boundaries for urban development and the city’s functioning over time.

On a Nolli type of map (showing only buildings), the buildings in Skarpnäck appear not unlike the buildings along Strandvägen, but (and this is an important but

) on the cadastral map (showing only property lines), the property structure for the monumental and airy Skärholmen appears exactly (!) like the small-scale and narrow jumble of buildings in Skarpnäck.

The residential architecture in Skarpnäck certainly has variety,

and thus avoids looking as repetitive as Skärholmen, but this is a consciously composed variation, it is a diversity that a single architect has total creative control over, so to speak: not only in individual blocks

—as is the case on Strandvägen—but also in whole clusters of blocks.

If one-block-at-a-time was all that the era could handle regarding control (or the guise of control) over the architectural appearance along Strandvägen, many decades later it became possible to handle so much more when it was time for Skarpnäck. In Skarpnäck there was no qualms about carrying out not only juridical and economical but also aesthetic control over almost the entire district

all at once, in one and the same project.

Which means that there are no property lines or firewalls in Skarpnäck that divide buildings into smaller bits that age and change at a different pace. Which in turn means that Skarpnäck, just as Skärholmen, will be perceived in the future as a deader

environment than both Strandvägen and Gärdet—despite the ambition in Skarpnäck to build with more variation, to be more picturesque.

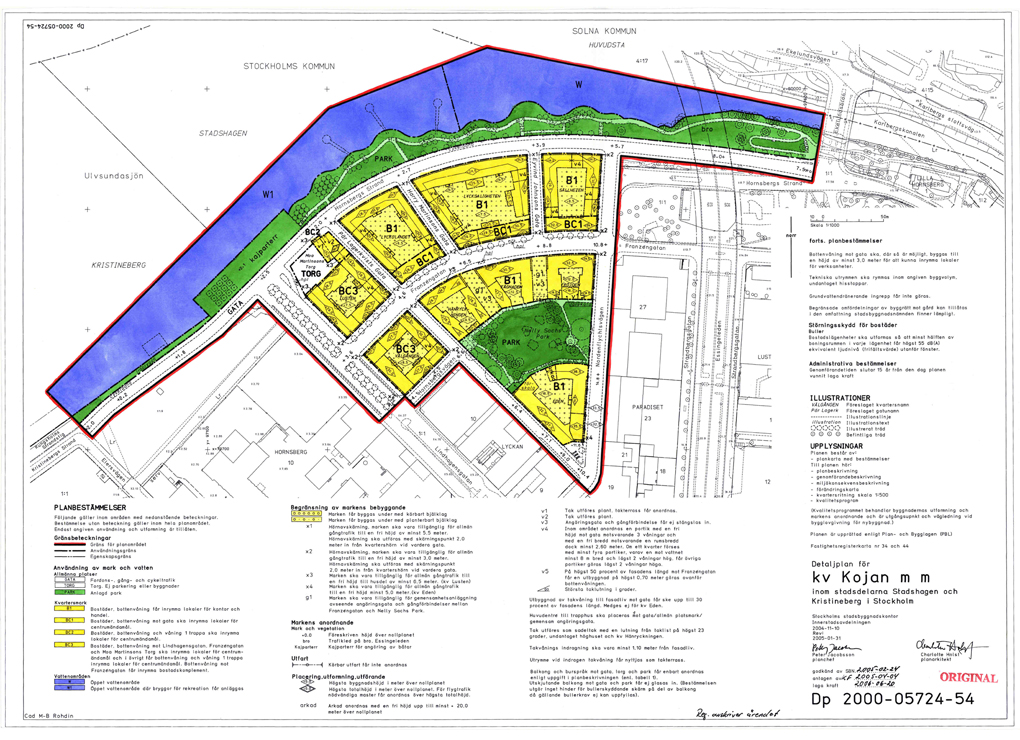

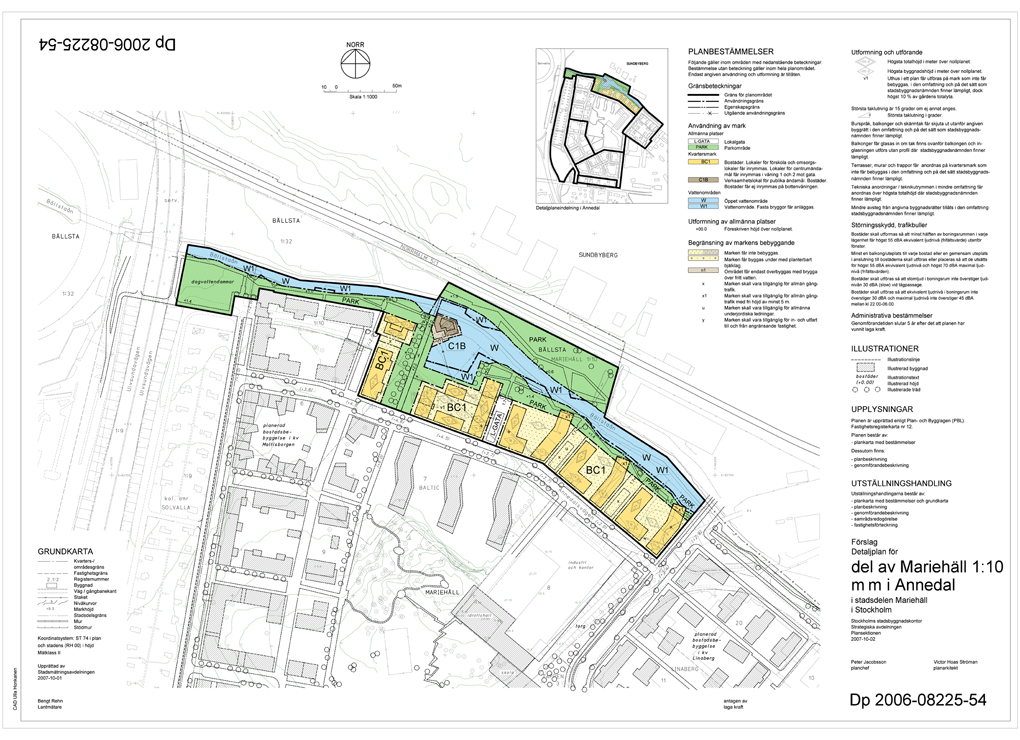

Hornsberg and Annedal

Thus far, we have seen a series of clear-cut and pure example types, with a clearly marked historical movement and direction. But they are all historical examples: Skarpnäck is now thirty years old.

So, what is happening today? What aesthetic and what ideology dominates when we build in our time? Do we construct buildings-in-a-park or not-buildings-in-a-park?

Neither-nor and both-and, it turns out:

Skarpnäck became in some respects an endpoint in this development. After Skarpnäck a lot of buildings have certainly been constructed in and around Stockholm. But without any feeling of aesthetic advancement or clear ideological direction. These days one builds eclectically, one constructs both buildings-in-a-park and not-buildings-in-a-park. Anything goes. Want to build a high-rise in the middle of the city? No problem. Want to build an inner-city-looking grid of urban blocks far from the city? No problem. Want to build both high-rises and corridor streets in the same area? No problem! Do as you wish, but only if you accept the juridically imposed conditions of property production that came out of the late-modern period.

How buildings look and how they function no longer matter at all. The only (!) thing that still appears to matter, the only thing architects and planners will still unite around, is their age-old phobia of property lines: properties should always be very big if it is possible. Size (still) matters. Size always (!) matters.

In their daily practice, architects and planners prefer as much as possible to avoid feeling they should account for someone else or something else when designing, to avoid feeling that they must address urbanity and city life on adjacent streets and/or parklands, to quite simply, as far as possible, avoid property lines. Or at least pretend that in the city there are no property lines.

Architects always think of a city plan as a Nolli map; think always of a city plan as a physically manifested building mass and physically manifested in-between spaces and empty spaces; never think (never want to think) of a city plan as an abstract entity, as law, as property formation and plot boundaries.

Architects always prefer to avoid placing a building exactly at the edge of a property. If there is space for it, the architect’s first and strongest impulse is to design freestanding, architecturally independent building complexes (palace,

villa,

housing area,

building-in-a-park

...). With the emphasis on freestanding.

Honestly, deep within, architects do not like the city. Deep within, architects do not like narrow city plots. On city plots architects never feel fully free to design in splendid isolation.

Architecture on a city plot will always—it lies in the nature of the beast—be a compromise between the city’s and architecture’s underlying conditions. The city always wants something other than what the architect wants. The architect, deep within, never wants the same thing that the city wants.

Horror limitis) in the architectural journal Kritik, Stockholm, no. 24, January 2015: Horror limitis (svenska)Kritik #24

The Trouble with the St. Erik’s Housing Estate

fearin the nominative singular, and limes,

boundaryin the genitive singular. Compare with the well-known term horror vacui. Thank you to Professor Eva Odelman at Stockholm University.

Illustrations

• Registerkarta (cadastral map), 1991: Stockholm City Council.

• City Plan Hornsberg (2000) • City Plan Annedal (2006) • Aerial photo from Digitala Stadsmuseet (Stockholm City Museum): Gärdet

• Aerial photo from Digitala Stadsmuseet (Stockholm City Museum): Skärholmen