The Murmuring City

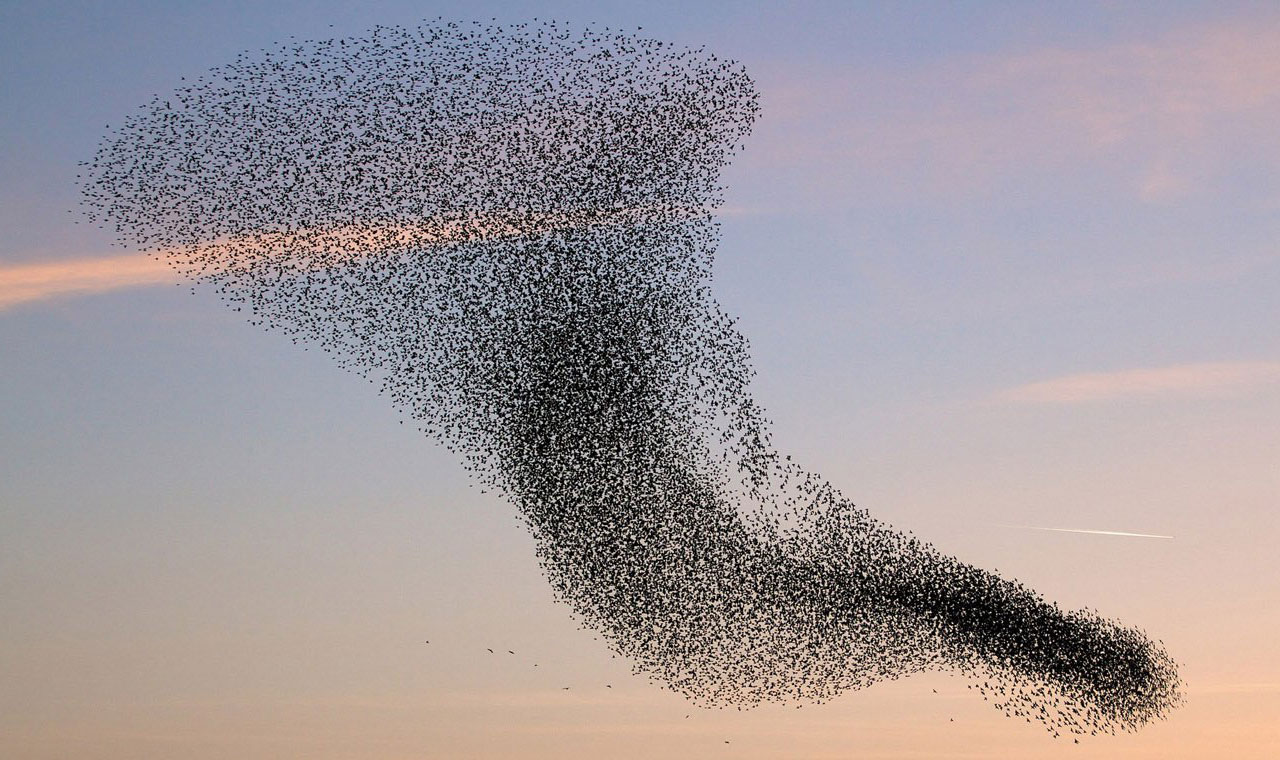

We have all at some point seen—either in real life, or at least as videos on YouTube—large flocks of starlings moving across the sky as if they were one big cohesive organism.

How on earth do they do it? All these tiny little individuals, with all their tiny little brains? How do they keep track of all their thousands of flockmates at the same time?

Scientists, of course, have long studied this natural phenomenon and have concluded that each individual in the flock has no need to keep an eye on every other individual in the flock, has no need to keep an eye on the behavior of the whole flock. In fact, it is enough for each member of the flock to only keep an eye on their immediate neighbors. By constantly adjusting its own flight speed and direction of movement, each individual bird keeps a given average distance from a small group of specially selected flying buddies.

A flock

of starlings, by the way, is called a murmuration

(of starlings)—a beautiful and poetic ornithological term, is it not?

The murmuring

flock, the murmuration, seems to be driven by an invisible herding dog back and forth across the sky, the complex movements of the flock giving the impression of having been directed by a demon director or choreographed by an artistically very talented choreographer genius guiding all the individual flock members—but the herding is an illusion, the overall shape of the flock is not formed by an external force acting on the entire flock but by the individual algorithmic calculations of hundreds, thousands of individual flock members.1

From one thing to another. Cities in all times—centuries, millennia—have emerged in the same way as flocks of starlings are formed: an outside observer is astonished by the unified mass of most cities, which seems to have been shaped by the extraordinary genius of a master planner, but on closer study the observer will find that although the master planner may have established a basic geometry in the horizontal plane (in plan

), in the form of a map, after that the same master planner has often enough more or less ignored the so called artistic expression of that which is being built on every individual plot of land, more or less ignored what happens in detail in the design of individual facades (choice of style elements, choice of color scheme, and so on). The master planners have contented themselves with a set of simple and, in the best sense of the word, banal geometric rules of the game that (like the corresponding simple and banal rules for the murmuring

starlings in the sky) apply to each individual and actor, each individual street corner, each individual property in the city separately.

And as long as exactly the same rules (the same overall limitations of geometry) apply to all players in the city, it doesn’t matter to each individual property and house owner what is being built several blocks away, it is enough for each individual property and house owner to monitor and keep an eye on what your nearest neighbors are building: the city murmurs.

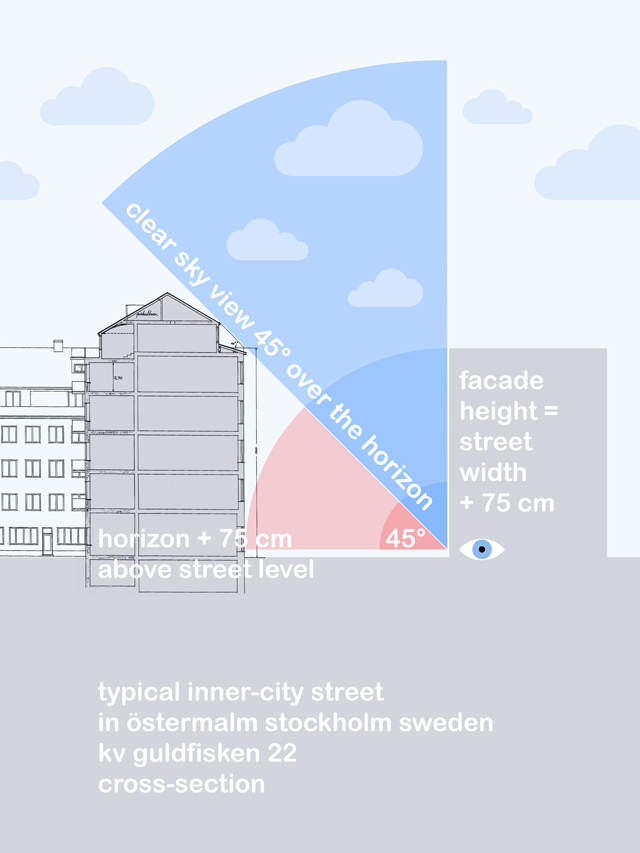

For example, in central Stockholm—a prime example of a 19th century gridded city and the murmuring

city of bourgeois liberalism—it has long been strictly adhered to (no exceptions whatsoever have been allowed), particularly one simple (and in the best sense of the word banal) limitation of geometry in the vertical plane (in section,

in elevation

), namely the pronouncement that the angle from the horizon up to a clear view of the sky over the building on the other side of the street must never exceed 45 degrees. This applies to all lines of sight that can be drawn from all windows in all rooms on all floors, from 75 centimetres above the level of the street (i.e., from an assumed location of the lower edge of the window frame on the ground floor) and upwards.

The same principle applies to determine the steepest possible roof slope for the building across the street: an absolute, irrefutable line of clearance and roof slope is drawn from the plot boundary exactly 75 cm above the level of the street, and across the street diagonally at an angle exactly 45° above the horizon to the opposite facade—or to put it another way, before the diagonal reaches the opposite neighbor’s facade, the diagonal can climb as high up the facade as the street is wide. A typical street in Stockholm is thus (not exactly, but in principle) square in cross-section; the building facades along a typical Stockholm street are (not exactly, but in principle) as high as the street is wide—or, more precisely, are 75 cm higher than the street is wide. Along a typical 18 m wide street in Stockholm’s inner city, the street’s building facades (up to cornice height

) are 18 m high plus 75 cm, a total of 18.75 m.

And once all the building plots along such a Stockholm street have been built as densely and as high as possible, without exceeding either the facade height or the roof slope limit, then at the same time, automatically, two very valuable qualities for city life have been added: there is both a sufficiently high level of development to create a customer base for local services, and at the same time enough direct sunlight and a clear view of the sky for everyone who lives and works along these streets, regardless of whether the streets run in a north-south or east-west direction. Both a dense cityscape with a palpable sense of enclosed space in its corridor streets, and at the same time a sense of airiness.

The best of both worlds, in other words. And imagine how much time and effort you save for the town planning office, and how much money you save for the taxpayers. In practice, things like building-to-land area ratio calculations and sun shadow studies become superfluous. There is also no need for subjective input in individual cases from, say, a meddlesome town planner. In practice, artistry becomes a superfluous characteristic of a town planner; designing

the urban space becomes superfluous in practice. Once an unambiguous development map has been drawn up, everything is in place that is required for the city’s individual players to be able to construct buildings more or less according to their own ideas, for the starlings to murmur,

for the city to come alive. Urban planning becomes mostly a matter of surveying, of keeping track of the geometry, of checking the angle of sight and the roof slope—but in a very strict way, with no exceptions whatsoever.

The cities that will murmur

the most in the future—both socially and culturally, as well as in simple economical terms—are those that find a way out of the prevailing urban planning ideals of the last hundred years or so, a way out of negotiated planning, out of the misguided artistic aspirations of planners, out of the assumption that each new urban plan should be unique, something very special and customized. But what about Sweden’s City Architects, all those top government officials running the planning offices of Swedish cities and municipalities, what about them? What about the artistic integrity of town planners, what about their scope for free artistic creation in each individual case—if a murmuring,

more nineteenth-century regulatory framework for urban planning were to be revived globally?

Well, what about them, one might ask. Apart from concocting authoritarian and tendentious quality programs

and other silly things, the planners of our time seem to be mostly concerned with taking every chance they get when urban planning

to put as much arbitrary nonsense into their town plans

as they can.2 If the architects of town planning offices would not accept considerable limitations on their artistry

when conceiving their new urban plans, if they would therefore go on strike, then surely surveyors would have to take over the daily routine—it would be as simple as that.

I certainly understand what you mean, Lars, I understand your question to me,3 I really think I do, but I am simply, rhetorically, bouncing your question back to you:

In the murmuring city—La Ville Murmureuse (to paraphrase Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse)—what kind of planning work necessarily requires a degree in architecture? What irreplaceable architectural quality can a town planner really be expected to bring to a building project in the city, and what is the irreplaceable architectural quality that the architect of an individual building project cannot bring? In The Murmuring City, what kind of planning work currently done by architects would a surveyor not be able to do?

Appendix 2023

It has recently come to the attention of the present writer that in the original Swedish text the way in which I use the expression murmuring

starlings (a flock of = a murmuration

of starlings) as a metaphor for urbanity (not only in English but also in Swedish: the murmuring

city—den sorlande

staden), seems to have inspired Mikael Parkman, a student at the School of Architecture at Umeå University (UMA), to title an English-language academic work Murmuring City—Banal Architecture (Thesis report, 5AR522, Mikael Parkman, UMA5, Studio 10, 2022). The above article is included in the sources that Parkman cites in his footnotes.

Incidentally, Mikael Parkman lists several articles by the present writer among his sources, among others the article Urbanitet, vad är det? eller hur man räknar ut urbanitetstalet u

(Urbanity: What Is It? or How to Calculate the Urbanity Index u

), published in the architecture magazine Kritik, Stockholm, Sweden, no. 32-December 2016, in which the Prologue

about a well-known painting by the surrealist René Magritte (Golconde, 1953) inspired Parkman to create a series of ambitious photomontages published in the same magazine some years later, in Kritik no. 48-December 2021, under the heading En gatas anomali

(Anomaly of a Street

).

45° över horisonten(

45° Over the Horizon) in the architecture magazine Kritik, Stockholm, Sweden, no. 45-June 2020.

Den sorlande staden

More about cities that

murmuron this website:

Den osynliga handen

More about Mikael Parkman on this website:

Urbanity: What is It?

The Urbanity Index u

urbanitythan, for example, the floor area ratio FAR. A list of links to all articles in this series:

About the Urbanity Index u

Illustrations

• Typical inner-city street in Östermalm, Stockholm, Sweden. Cross-section (1937, kv. Guldfisken 22). Montage: Mikael Askergren, 2020.

Footnotes

How do birds avoid colliding?), a news item signed by the editorial staff of Illustrerad Vetenskap (

Illustrated Science), Stockholm, online edition, Jan 09, 2009.

arbritrary nonsense,the article by Mikael Askergren on the St. Erik’s residential area on Kungsholmen in Stockholm and the Husarviken residential area on Norra Djurgården in Stockholm: Ärtan-pärtan-piff-paff-PUFF (

Eeny Meeny Miny Moe), in the architecture magazine Kritik, Stockholm, Sweden, no. 45-June 2020, and Happy Accident, Kritik No. 42/43-November 2019.

Vem skall bygga staden?(

Who Shall Build the City?) in the architecture magazine Kritik, Stockholm, Sweden, no. 45-June 2020. In his article, Lars Marcus comments on Mikael Askergren’s article on the St. Erik’s residential area in the same issue of Kritik, Ärtan-pärtan-piff-paff-PUFF, in which it is stated:

The architectural profession should not be involved in urban planning at all.But then who should plan cities if architects don’t, asks Lars Marcus:

I realize that today’s architects are not at all equipped for this, but I think it is an architectural problem, what else would it be (open to suggestions).