Villa Spies

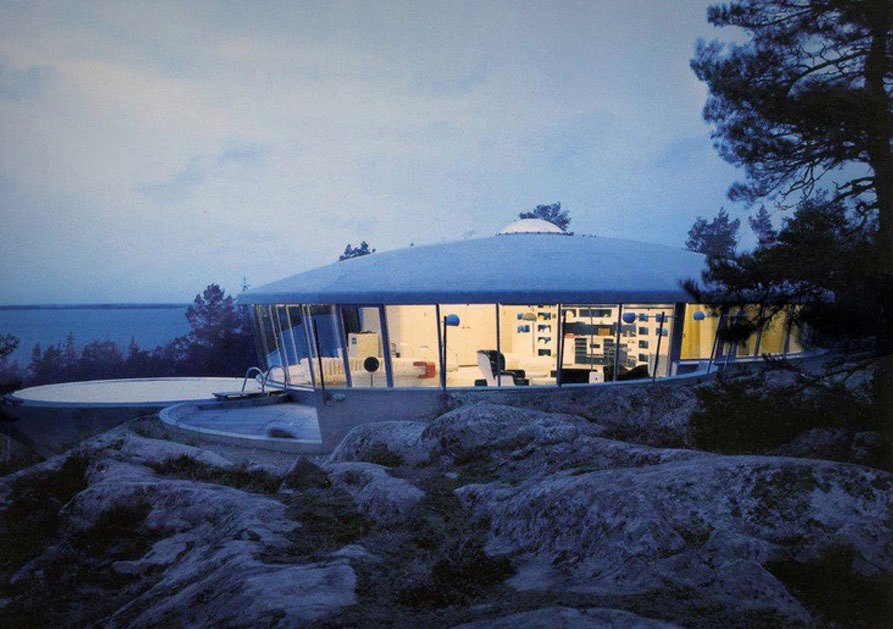

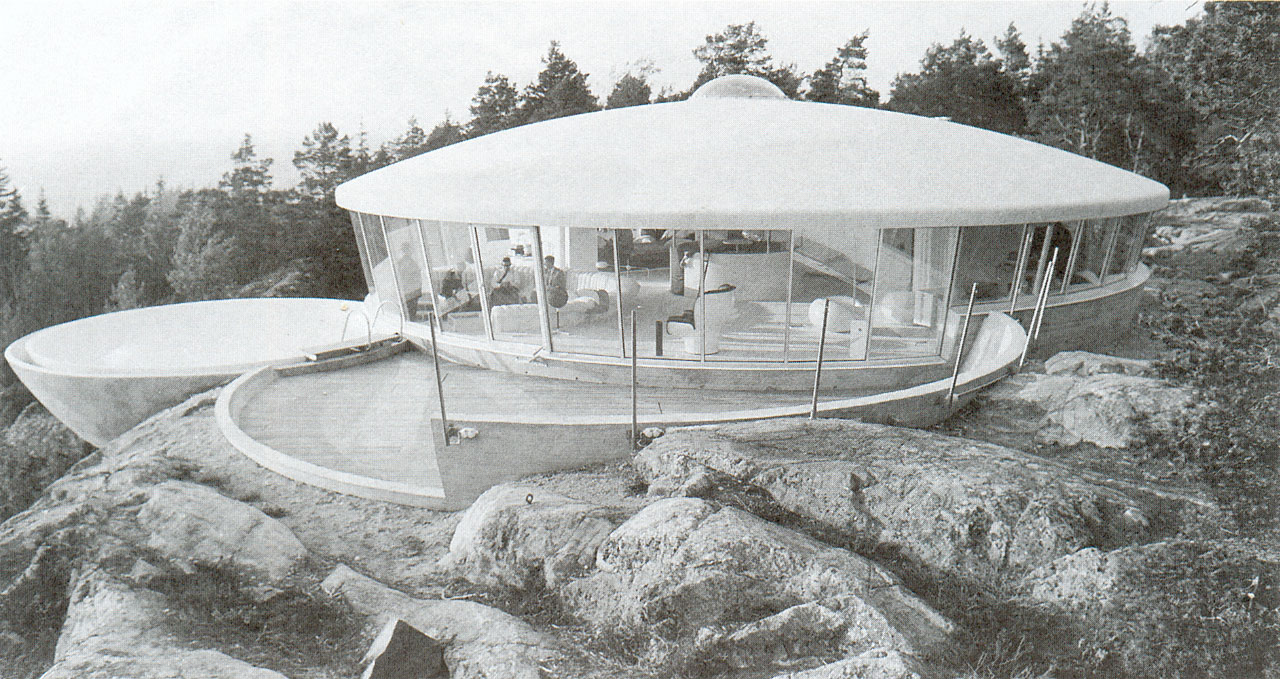

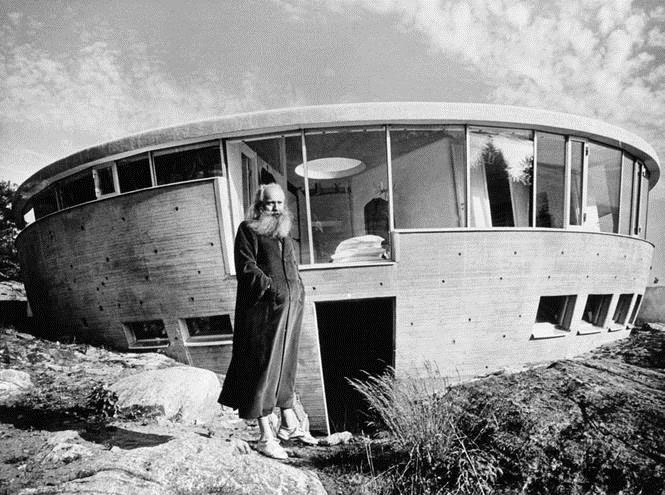

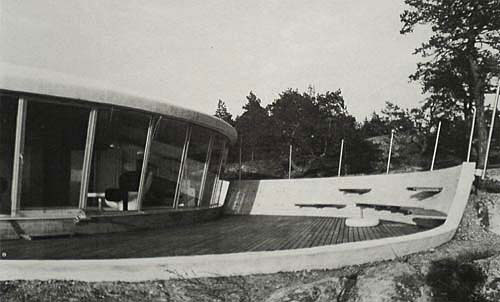

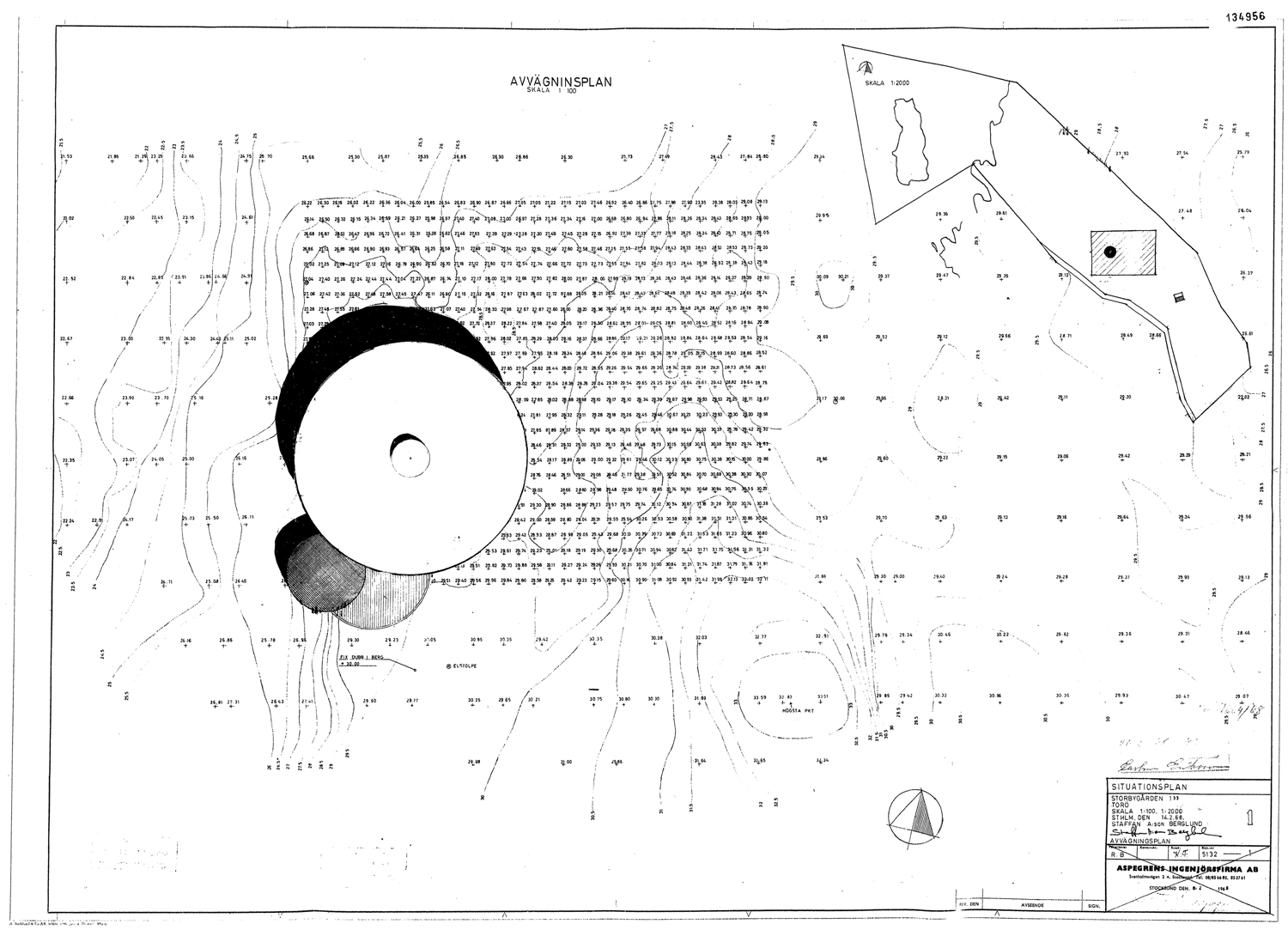

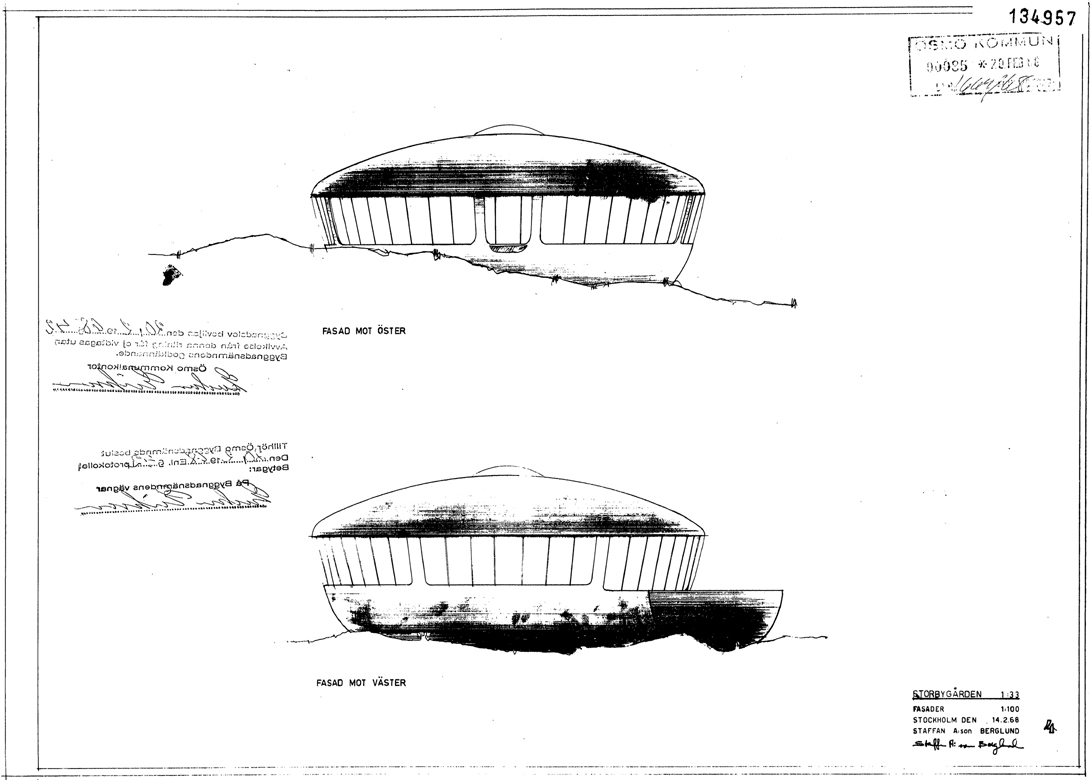

Welcome to the pleasure dome. Welcome to a futuristic, hedonistic summerhouse designed in 1969 by the young Swedish architect Staffan Berglund for the wealthy Danish visionary and business genius Simon Spies. It is located on the crest of a rock at Torö, Sweden, overlooking the ocean and the archipelago that surrounds Stockholm, the Swedish capital.

Pleasure Dome

In 1967 an architectural competition is arranged by the Danish travel agency and charter airline Spies, Scandinavia’s greatest success story of its day in the travel industry. (The ie

sound in Spies

is pronounced like ee

in speed

or ea

in peas.

) A number of architects from Scandinavia and Spain are invited. The task is to design a prototype for a mass-produced vacation house for Scandinavian tourists traveling to Spain who do not wish to stay at a traditional hotel. With growing affluence in post-war society, Simon Spies, the company’s legendary founder and visionary, envisions all tourists in the future, not just the wealthy, to expect more than just a hotel room, a bed, a tv-set, and a continental breakfast. A double room, even in the nicest of hotels, soon becomes claustrophobic, especially at holiday areas that perhaps include little more than a beach and some palm trees, and lack any cultural offering.

The Swedish architect Staffan Berglund wins the competition. His proposal is for a circular, dome-topped, single-story house, made entirely of plastic. The vacation house is adaptable for any site—for the beach, as well as the mountains—and it is meant to be exciting, an experience in itself.

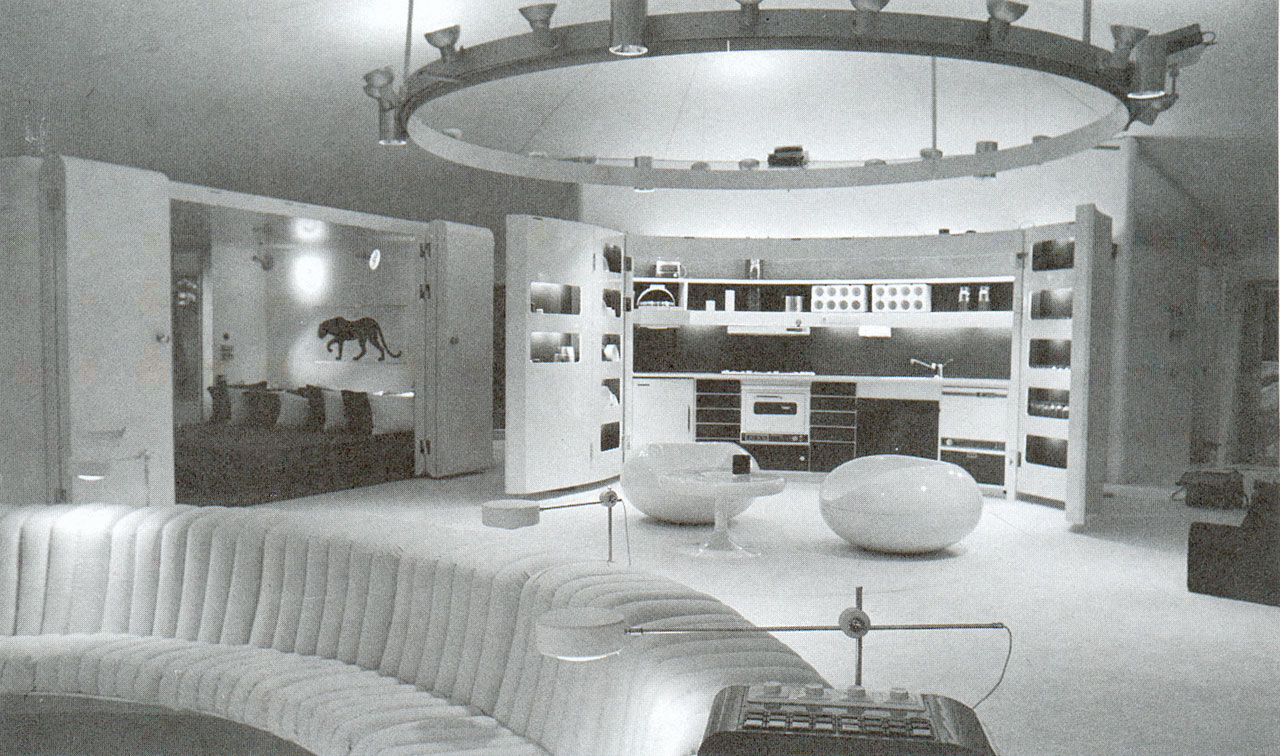

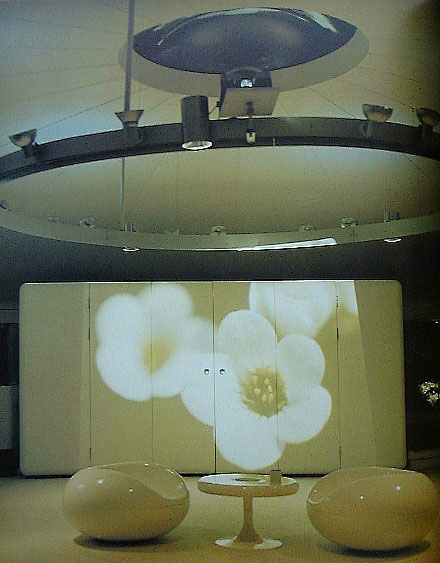

A system of movable screen walls allows the same open-plan prototype to serve both honeymoon couples and families of five. The movable walls are not really walls

in the normal sense, though. They consist of freestanding closet and storage sections as well as light folding screens of corrugated cardboard that never touch the ceiling. The idea is that by providing cordless headphones to those who wish to listen to music or watch tv, it is possible for one member of the family to take a nap behind a cardboard screen while others are up and about. Heavy inner walls become superfluous. An exception is made for the master bedroom, which is totally separated behind soundproof folding walls.

The kitchen is proposed to be equipped with disposable plates and cups, which at the time—in the sixties, before the energy crisis—is still not viewed first and foremost as presumptive waste, but rather as something which frees up time, and offers families on holiday a greater freedom of movement: to arrange a picnic becomes less of a strain when the picnic basket is not weighed down by genuine porcelain, silver, and real glass. Families on holiday can avoid time-consuming meal preparation if so desired by purchasing meals delivered by the travel agency—even gourmet meals which otherwise take several hours to prepare. (The bouillon for a Potage St. Germain, as the architect points out, should boil for twelve hours.) Meals, prepared by the locals, can become a small industry for each holiday area, providing job opportunities and income from the tourist industry even in remote villages.

There will be no Spanish holiday houses. Perhaps the Spaniards become wary when they realize that the winning proposal will not automatically provide jobs for the local craftsmen and builders, nor makes use of local building materials. One may guess that Simon Spies sees no reason to get on the wrong side of the Spaniards, and cancels the project.

Staffan Berglund instead receives another commission. To design a house in Sweden for Simon Spies at Torö, in the southern part of the Stockholm archipelago. The Villa Spies (also known as Villa Fjolle. Fjolle

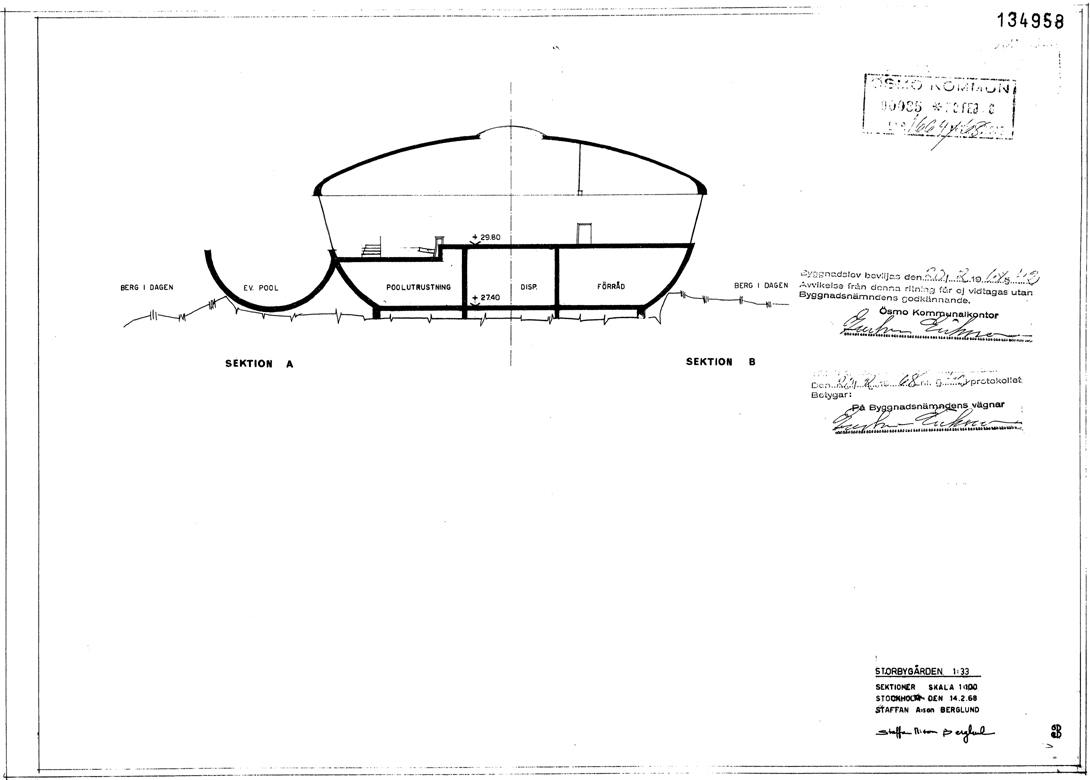

is a Danish word meaning silly, crazy, funny) is completed in 1969, and like the competition proposal, has a simple circular plan form. It is no longer a single-story dwelling, however, but instead a two level house, the lower level in the form of a bowl-shaped base of cast-in-place concrete. The dome consists of light, pie-shaped prefabricated elements made of plastic, only one decimeter (four inches) thick. These elements make up both the ceiling and roof, and together form a shallow, self-supporting dome. In the middle of the dome there is a pantheonic round hole covered by a smaller transparent dome. (The pie-shaped elements are handmade. Instead of carbon fiber reinforced, the plastic dome is fiberglass reinforced in the normal manner. In reality, development in 1969 has not yet reached as far as the visions of the fifties and sixties.)

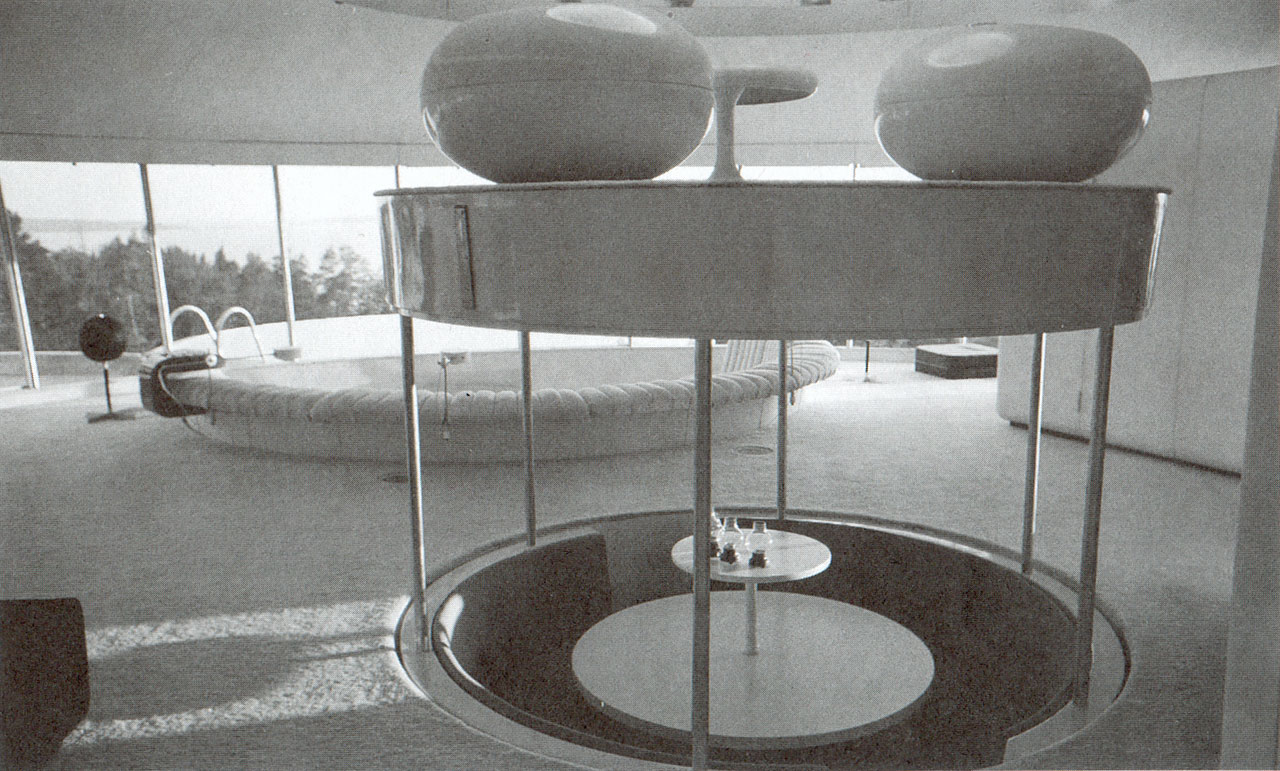

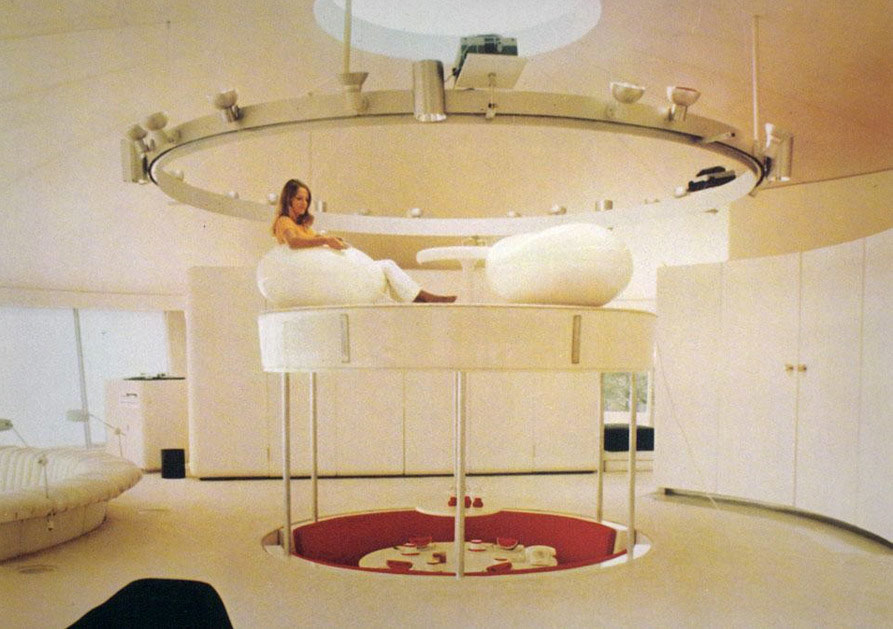

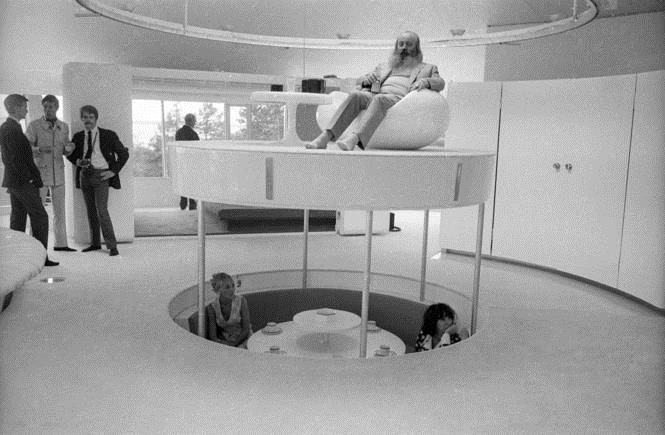

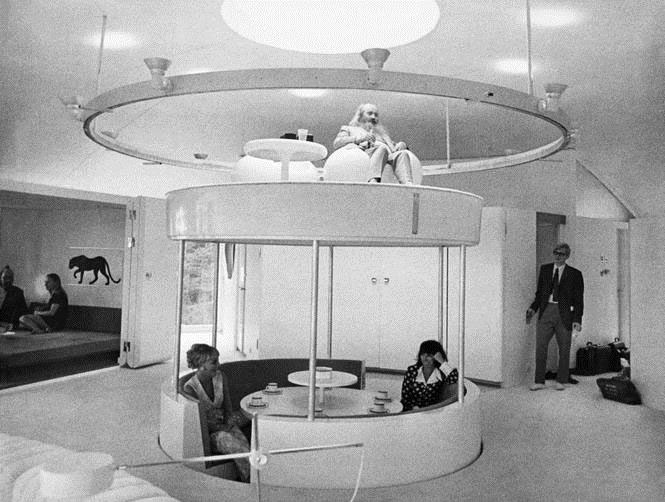

One socializes, cooks, and has meals all in the same large open-plan space of the upper floor. Downstairs there is a dining group with a round table and fixed seating which by the push of a button can be raised up to the main floor in fifteen seconds. This in turn causes the round piece of the upper story’s floor that constitutes the roof

of the seating group to rise up towards the round pantheonic hole in the domed ceiling. Those who remain in the chubby white plastic lounge chairs on the roof

of the seating group will then, when the dining group reaches its up-position, be able to look out over the bay and surrounding islands through the transparent dome which covers the hole.

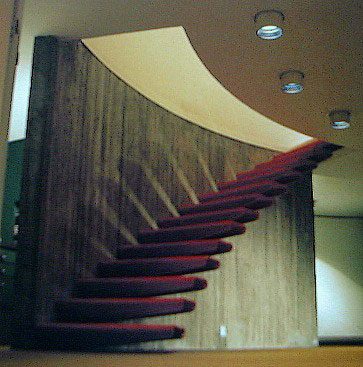

As in the competition proposal, one sleeps in a separable bedroom behind insulated folding walls. Behind the kitchen and stairs, next to the upper floor entrance, there is a bathroom (with a very light, vertically adjustable plexiglas washbasin and a bright red bathtub, both made of plexiglas). Guests staying overnight could be accommodated behind light cardboard screens, as in the competition proposal, but there is also a comfortable and more private guest room and bathroom downstairs. (The basement floor includes boiler room, guest room, bathroom, extra kitchen, and an additional entrance door.)

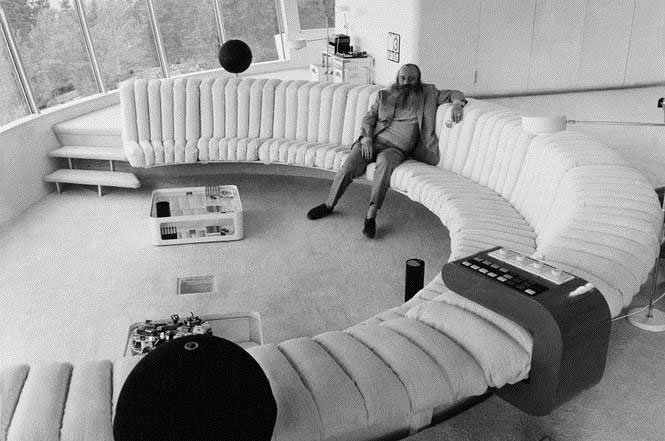

All the interior fittings upstairs are white, as is the wall-to-wall carpet. The only exception is the very seventies warm-red color of the control panel—conveniently located on top of the back of the long white curved sofa—from which all of the house’s technical finesses are monitored and controlled. All windows are furnished with motorized shades which block out all natural light. Stationary slide projectors can project images onto the white shades, walls, floor and ceiling simultaneously. There is a choice of slides portraying anything from scenic landscapes to works of art. The projection of works of art replaces real works of art. Recessed in the slit along the outer perimeter of the dome where the shades and their motors sit are twenty speakers, mounted invisibly, at equal distances all around. Music, for example, or the recorded sounds of lapping waves can even be cast into movement,

wandering from one invisible speaker to another, round and around the house. (It is not the case, however, that the double bed or the whole house rotates, as the tabloids proclaim, and many locals still believe.)

When not using technology to unite everyone in the house in a collective sound environment and slide-show experience, technology can also be used to create privacy. In 1969 there are no cordless headphones on the market for home use, neither for the stereo nor tv, but a cordless system is specially built, so that several people engaged in separate activities—even music-listening and tv-watching—can use the open-plan space upstairs simultaneously without disturbing each other. This, and many other unorthodox solutions originally proposed in the competition entry turn out to work very well in real life.

Simon Spies likes the new house and spends much time there. During his stays the villa is used both as a private vacation dwelling and as a place of work. The house becomes a significant part of Simon Spies’ business activity. In this way, the Villa Spies functions in the same way as manors and estates had done for centuries for the aristocracy, or as the merchant house did in commercial towns. (They served both as a home and as the heart of the owner’s professional and business entertaining activity.) The Villa Spies is called by Simon Spies himself the world’s best conference facility.

The business meetings take place in a relaxed atmosphere on the long, curved, white sofa. These meetings often turn into social gatherings with dinners in several courses. At these and other special occasions, instead of using the kitchen facilities on the main level, the lower level’s extra kitchen is put into service. The round table of the seating group lift is set downstairs. By the push of a button, like magic, the seating group appears upstairs.

The fixed seating accommodates no more than six people. This is for a reason. Even if, occasionally, larger publicity events and receptions take place in the villa, Simon Spies believes that one should not be too many at the dining table. Everybody should feel they are part of the same discussion. No one should feel outside. The limited seating of the dining group works as an excuse to avoid having too many people over for dinner or business: Sorry, there simply is no room for more people.

Between the courses the guests stretch their legs in the cool summer night on the terrace while the seating group disappears down under the floor so the table can be reset. After dessert the seating group disappears out of sight again. Or the whole gang stays seated and travels with plates and cutlery down to the lower level and helps load the dishwasher before taking the seating group lift back up to the piano nobile again.

Architects-Against-Architecture

The Villa Spies is widely publicized in the early seventies in the years after its completion. The media are often invited to attend parties and events, and the public shows great curiosity and interest in both the unconventional house and the lifestyle of its tycoon owner. This interest gives both Simon Spies and his business a lot of invaluable free publicity. Still today most Stockholmers have at least a vague, if sometimes misinformed notion of the villa: Oh, of course, you mean the round house that rotates.

Despite its purism, the house comes across as more sensual than ascetic in spirit. And despite its theatricalities, it is intimate and livable. The total lack of traditional status

interior decor, and the villa’s—considering who built it—small scale and unpretentious countenance (different does not equal pretentious) are all engaging features. But the Villa Spies is never presented in Sweden’s professional architecture magazine Arkitektur. Nor is the villa included when, in 1978, the National Association of Swedish Architects (SAR) puts together the English language The SAR guide to Contemporary Swedish Architecture 1968-78.

It is likely that the Villa Spies alludes too strongly to a glamorous, affected hedonism—a cosmopolitan lifestyle which too often prefers cocktail parties and Burt Bacharach over Nordic melancholy, and white plastic and plexiglas over natural materials—to be regarded as something serious

by the post-May 1968 Swedish architecture intelligentsia. Doing business with Franco’s Spain is also considered suspect. The Swedish nation is urged by public figures and intellectuals to refrain from holiday travel to the Costa del Sol. For example, in Vilgot Sjöman’s 1967 semi-documentary film I Am Curious—Yellow, tourists returning from Spain are confronted at Stockholm’s international airport by the film crew and interviewed about their choice of holiday destination. The interviewees try to appear collected and unaffected while subjected to the camera’s and leading actress Lena Nyman’s insinuating obtrusiveness. However, the government of Sweden does not officially boycott Spain; it is already considered to be moving gradually towards democratization. (Franco dies in 1975.)

As it turns out, neither the smart white wall-to-wall carpeting nor the Spanish connection motivates the total radio silence and boycott by the architectural media. The seating group lift is at fault. Or more correctly, the lift’s way of dividing a modern household into a feudal upstairs and downstairs, with staff below preparing meals and setting the table, is seen by the times as an anachronism and indecency, as an unacceptable mockery of the egalitarian pretentions of modern architecture. The irony of this reaction is that the seating group lift is actually the realization of an old dream of the very architectural establishment that finds the lift offensive—the dream of a flexible

architecture.

Thanks to architectural flexibility, thanks to the seating group lift in the Villa Spies, a modest (different does not equal pretentious) house functions as well, if not better, than a house two or three times as large. A conventional summer villa used for business-related entertaining and containing the normal suite of library/lounge/dining room would require at least twice as much space, would cost more, would use up more natural resources, would create more waste, and would probably damage large volumes of the archipelago’s typical, smooth, picturesque heaving bulges of gray and pink bedrock. The seating group lift is not an expensive construction. The lift mechanism is a mass-produced scissor table for industrial use—a modest investment compared to what the construction of a separate dining room and lounge would cost—but at the same time hardly a solution for common social housing. Philanthropists have for a long time hoped for flexibility as a means of achieving democratization

in architecture. It just never seems to work as intended.

(Note. For instance, there were attempts after World War II to dissuade the Swedish people from furnishing the largest room of their council house or apartment as a finrum, a best room,

which was never used except on special occasions for entertaining. In new post-war social housing developments there were experiments with a flexible

combined family room/kitchen/living room both for everyday and special occasions. As it turns out, the tenants often chose to furnish one of the bedrooms as a special finrum instead.)

When architectural flexibility for once actually works

—since, as in the case of the Villa Spies, it is motorized (one would otherwise have to drag the dining table and chairs in and out all the time)—it becomes apparent that flexible architecture

will never become a virtue successfully imposed upon the lower classes by architects and middle class intellectuals, but will by default, if anything, be an occasional toy and luxury of the rich.

Philanthropy in architecture is in itself a contradiction of terms. All architecture is a mockery of the principles of well-meaning, philanthropic architects. Without exception, the history of architecture consists of buildings erected by powerful individuals or institutions at the expense of others (pyramids, cathedrals, castles, palaces). Mankind’s striving for emancipation has been a struggle against these institutions and, not surprisingly, against their buildings. It is no coincidence that the Bastille is torn down during the French revolution, or that the collapse of the Warsaw pact coincides with the demolition of the Berlin wall. Mankind’s struggle for equality and freedom is the war against architecture. With the abolition of the death penalty, with the abolition of the right of society to sit in judgement over the life and death of its members, it is no longer possible for architecture to serve as an expression for the philanthropic aspirations of modern western democracies. Architecture is not democratic.

(Note. I hereby take the somewhat flippant liberty in this context to put the term democratic

between quotation marks, i.e. I take the liberty to use the term as carelessly and incautiously as most people do all the time. Often enough the word democratic

is used merely as a synonym for the adjective good

—making anything not being to one’s liking or in the interest of one’s social class or field [Bourdieu] undemocratic.

To others still democracy

is equivalent with freedom,

suggesting that the lawmakers, institutions, and authorities in democratic societies are, in a very idealized way, subject to the will of each individual in a much greater degree than is actually the case. This popular notion of democracy could be seen as closer to literal anarchy—a society without centralized power, without government, without institutions—than to matter-of-fact majority rule. As long as the influence and power of the institutions of society over the individual are not challenged by the masses, it is not in the interest of the institutions of matter-of-fact democracies to sort out this misunderstanding.)

Architecture always was, and by default always will be, the prerogative and privilege of the rich. To build is expensive. The accumulation of capital and power—inescapably at the expense of someone else—is a prerequisite for any work of architecture. Accordingly, buildings with architectural merits cannot possibly serve as precedents for architects whose ambition is to serve the great masses of a post-plutocratic society. There no longer exists a direct relationship between a building’s merits as architecture and its merits as a precedent for architectural practice.

As a model and precedent, the architectural profession prefers the middle-class wholesomeness of the Villa Drake in Borlänge—designed by Jan Gezelius and, like the Villa Spies, built in 1969: a tall, slender wooden house with mullioned windows that becomes something of an icon for good housing design in Sweden during the seventies and eighties. The Villa Drake graces the cover of Arkitektur, no. 3, 1972.

As mentioned, to build requires a significant accumulation of capital and resources. To build a villa even of ordinary size, like the one in Borlänge, also requires such an accumulation. But nowhere does the Villa Drake reveal the dangerous secret of architecture—that even with a moderate accumulation of resources there is the power to exercise violence, the power to be architectural. This is why the Villa Drake is possible as a model for the politically correct seventies and eighties.

Thus, in the case of Villa Spies, it is not really the business relations with Spain which provoke the great majority of organized architects in Sweden, but instead the lack of desire to conceal one’s wealth, or rather the lack of desire to conceal the initiative that wealth gives to realize and give physical form to one’s ambitions. In the case of Villa Spies, it is not the lifestyle or values of its commissioner that are really offensive. It is the shameless audacity of using one’s capital and resources to build an environment congenial with one’s personality and desires. The audacity of making architecture. This is all so provocative that the times cannot allow the publication of Villa Spies.

Deadness

life,which we associate with the pharaohs of Egypt or the city-states of Greece, but instead the graves and temples, the buildings of

death.The trivial world where daily life is lived and the daily bread is earned—built of wood, mud, and reeds—is lost. Grave monuments and temples, the houses of the dead and of superstition—carved out of marble and granite—remain.

Life,and the material welfare of the masses, becomes the measure for judging the success of a particular society. However, the hallmark of architecture—as opposed to ordinary and trivial buildings which are neither designed by architects nor erected by powerful individuals and institutions—remains its deadness. Architecture continues to manifest

death,the immaterial, the already dead, or dying phenomena and institutions that cannot be saved—as a panegyric, or with a vain hope of immortalizing that which cannot last. The cult is already dying when the most magnificent temples and cathedrals of man are being built. The theaters which are most interesting architecturally all belong to epochs when the art of drama is fairly uninspired—epochs when the theaters and museums fill other needs than serving the arts, epochs when erecting great architecture is used by declining powers, convulsively and in vain, to make everyone, including oneself, believe the system is still vigorous and vital.

Architecture and drama are sister arts, but like sisters they fail to bring out the best in each other: indeed [...] it might seem they have avoided each other’s company. The great formative minds of drama—the Greek playwrights, the authors of the miracle plays, Shakespeare, Lope de Vega, Molière, Corneille, Racine—were all happy enough with the necessities of performance. Ibsen and Chekhov asked for little more. Strindberg’s preferredintimate theatrewas an ordinary room. And conversely, those theatres of most architectural interest—Greek theatres of 300-100 BC, Roman theatres from AD 100–300, the theatres of renaissance Italy and of Europe and America between 1700 and 1875—all belong to periods when the art of drama was at low ebb.

—Simon Tidworth, Theatres: an Illustrated History, London, 1973.

to death.Sooner or later the heritage of architecture becomes without fail the museum (i.e. mausoleum).

death(i.e. the immaterial, like religion or the monarchy), and instead pledged devotion to

lifeand the buildings where

lifetakes place (to the material needs of the have-nots, to the design of commonplace buildings which were always disregarded as areas of responsibility for the powers that be).

Lifeand the material welfare of the masses, becomes the measure for judging the success of a particular society. The projection of architecture onto non-architecture has not, however, made the architecture of this century come more

alivethan that of previous centuries. The modern era has not been spared from building primarily for needs other than the material, the worldly, the measurable. Instead of lords and empires, ideas and ideals have been glorified. Formal concepts and social policies have been projected onto the trivial and cast in concrete. Instead of architecture becoming informalized, the informal has become architecturalized.

Necrobiosis—Necropolis—Necrophilia

Society changes constantly. The great philanthropic building projects of Western democracies—like large-scale social housing, or the redevelopment of city centers—already stand as grand mausoleums to the dead policies they were once meant to perpetuate. They stand above all as mausoleums to one particular idea; the idea that Architecture with a capital A could be living,

could be alive.

Death

is the fate that all masterworks of architectural history share. There is no greater compliment to a building than being embalmed (figuratively speaking), to be preserved for posterity. The deadness of architecture is a mark of nobility. Bringing disregarded buildings into the realm of architecture is an act of love, but the desire to do so is murderous.

Casualties

are unavoidable when the architecture establishment declares its affections. To love architecture equals desiring what is dead,

equals necrophilia.

Simon Spies dies in 1984. The present-day owner of the Villa Spies will not allow the public or the media inside the villa or onto the property. Distant and beyond reach, the characteristic dome, white from crushed marble is, however, still very visible from afar up on the crown of the rock, and a landmark for navigation in the waters around Torö—shimmering like mother-of-pearl, its cool paleness like the skin of a corpse.

Stockholm, October, 1996

Appendix to the Book 1996

Welcome to the pleasure dome. The Villa Spies makes a world and a reality we have managed to forget come alive again. In the sixties, before the energy crisis and its aftermath of massive economic and cultural setbacks throughout the West, the new still has a value in and of itself, an intrinsic value in a completely different way than it has today. The most optimistic believers from the school of progress are convinced that plastic will revolutionize the building industry, that carbon fiber will lower the cost of reinforcement dramatically, that more and more traditional building materials will be replaced through new technologies.

Electronics, plastic, and synthetic building materials are often associated today with the cold, the impersonal, the anti-sensual. This was not so thirty years ago. The Villa Spies is intended to function in a sensory and sensual way, to engage all the senses. It is for this goal that technology is put into use. And as often as the technology of the Villa Spies is meant to stimulate our senses, it also provides the possibility of eliminating undesired sensory stimulation. And it all works.

The villa has never been remodeled or added on to, and the original interiors and furnishings have been preserved. The plastic structure of the dome is still in perfect condition (inspections and tests were carried out in 1988 by Thorkild Rand, senior professor at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm [KTH], who was also the dome’s engineer).

A few years ago, while rummaging through old papers, I find an article with lots of color photos that as a teenager I tore out of a magazine and saved. The article, from 1974, is a feature presentation of the Villa Spies, one of many examples of the extensive coverage by the popular press in the years following the villa’s completion (Femina, no. 8-1974). I relive my first delight, but it occurs to me that I have never ever during the years that have gone by, during my years as an architecture student or afterwards, heard the villa mentioned, let alone seen it published in any serious architectural context. Many inconsequential boxes and heaps of stone have at least received a footnote in the history of architecture, but in architectural circles the Villa Spies is still officially a non-building. Why? Why this total radio silence?

After making contact with the villa’s architect Staffan Berglund—who still lives and practices in Stockholm—I write a text about the villa for the 1995 annual architectural essay competition organized by Arkus, a non-profit foundation in Stockholm which promotes the continuing education of Swedish architects. My essay does not win the competition, but receives an honorable mention, and is chosen for publication in the booklet Seven Essays on Architecture (Arkus, Stockholm 1995). It is that same essay which has been expanded (and in parts rephrased) for the architectural monograph of 1996. Unfortunately, much of the material about both the house and the competition proposal could not be found in the architect’s archive. In my essay for the book, I have therefore relied on the architect Staffan Berglund himself as the main source regarding the house’s early history and inception.

The architectural monograph Villa Spies (Staffan Berglund’s Villa Spies) was published in 1996 by Eriksson & Ronnefalk Förlag (E&R Förlag), Stockholm, Sweden (ISBN 91-972660-0-0). The book consists of an abundance of photographs from the archives of the villa’s architect Staffan Berglund, architectural drawings and renderings, plus an essay by Mikael Askergren (in English and Swedish—English translation for the 1996 book by Michael Perlmutter).

Appendix to the Web Edition 2008

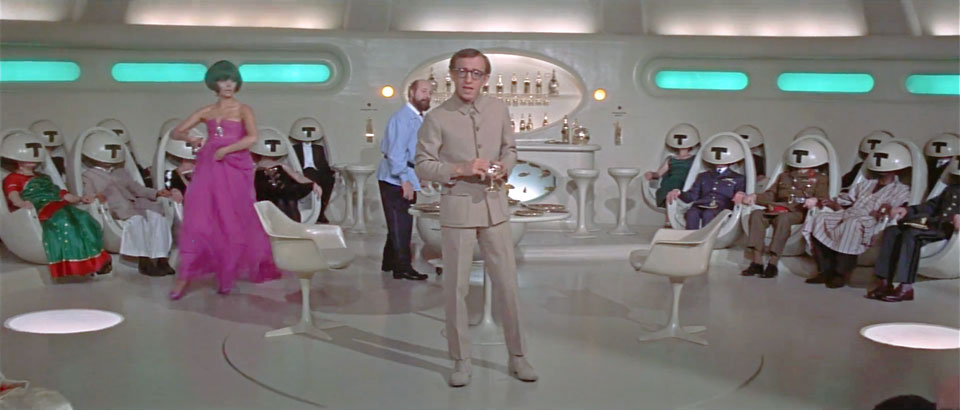

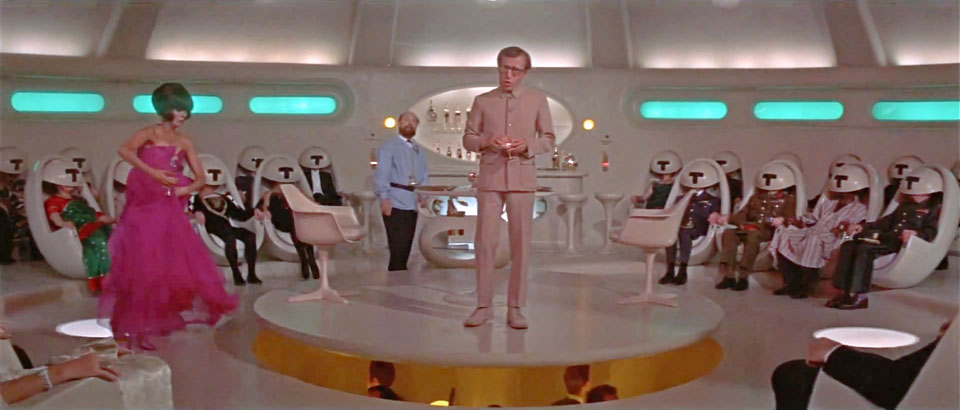

This changes everything. A short film sequence from the 1967 unfunny James Bond parody Casino Royale changes everything I thought I knew about the Villa Spies (also known as Villa Fjolle, the futuristic, white, domed villa of Danish travel business genius Simon Spies, at Torö, just outside Sweden’s capital city Stockholm):

In the very last minutes of the long (much too long) film, Woody Allen in the role of Dr. Noah,

James Bond’s evil nemesis, and his attractive female hostage step inside a peculiar domed space which in many ways resembles the interior of Villa Spies—because suddenly, without warning, a circular section of the floor is lifted up towards the ceiling, with Woody Allen, standing on the platform, making his big nemesis speech as he is lifted higher and higher, and closer and closer to the apex of the shallow white dome. Simultaneously appears, from below the soaring platform, a small men’s singing group in dashingly blue tuxedos, surreally accompanying Dr. Noah’s speech with song. After the short speech is finished, the round platform (and the singing group) is lowered into the floor again.

The scene only lasts for a minute, but it changes everything all the same. Because it all fits. The time line (the movie came out in 1967, the villa was finished in 1969), the looks (white dome, white furniture), and—not least—the gadgets (a movable platform, for goodness’ sake!). This movie set simply must have been a direct inspiration for the architect and his team—consciously or unconsciously—when designing the remarkable Villa Spies/Villa Fjolle. Yet, the Casino Royale movie set was never mentioned by architect Staffan Berglund when I interviewed him 1995 for my essay Pleasure Dome,

which later would become the backbone of the illustrated architectural monograph, published in 1996.

But, more importantly—nor was this movie set mentioned by architect Per Reuterswärd when, in 1998, he accused Staffan Berglund of not paying tribute to, or giving credit to everyone involved in the villa’s design. Reuterswärd, for one, claimed to have been instrumental in shaping the villa. Staffan Berglund responded to this claim by confirming that Reuterswärd was indeed hired as a consultant at one point (Arkitekttidningen, no. 12-1998).

However, methinks Reuterswärd et al. should squabble less between themselves, and instead generously invite some new members into their group; members until now completely unknown to us outsiders, namely the art directors of the 1967 James Bond parody. But, just as there were many—too many—directors involved in the filming, there is a confusing number of art directors and designers listed in the film’s credits. So I invite anyone who reads this to enlighten me, and to enlighten us all. Who designed this particular set? Please write to me.

Who knows, perhaps it was Simon Spies who went to the movies one night and was inspired by what he saw on the silver screen. Perhaps the inspiration from the film came via Simon Spies himself? Does anyone who reads this know? Please write to me if you do!

This my very recent discovery (just weeks ago, in early 2008) does not in any way mean that everything that architect Staffan Berglund told me (in 1995) about the villa’s early history necessarily must be untrue. The way I see it, this discovery of an, until now, unknown pop culture reference merely shines new light on a process (the process of designing a house) which is always complex, and could never be reduced to simple causality and chronology where everything that influences the final design (and everyone) can be accounted for. In fact, my recent discovery only makes the villa’s history and conception richer and more interesting to me.

Pleasure Dome,is republished here on this website in 2008, with kind permission from the book’s publishers.

shimmering like mother-of-pearl, its cool paleness like the skin of a corpsedid not make it inside the printed book. This certainly morbid finale was the ending the author originally intended for the essay and for the book. But for some reason or other, in 1996, Mikael Askergren changed the ending at the last minute—which he has regretted ever since.

politically incorrect.The villa’s architect was ridiculed and sneered at by his mainstream peers for 25 years—until the publication of the book by Mikael Askergren.

The Uppers Organization

deadnessof architecture has been a recurring theme in Mikael Askergren’s work ever since the publication of the architectural monograph about Villa Spies. More by Mikael Askergren about death,

deadness,and architecture:

Lethal Architecture

Häpp!

Om Eurohus

Arkitekturens död