Submissiveness of Architecture—Submissiveness to Architecture

Confused and puzzled by the world’s disinterest, today’s frustrated architects find comfort and consolation in entertaining obscene fantasies. Mikael Askergren explains why, by way of contemplating, among other things, the architecture of Richard Wagner (i.e. the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Germany).

Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the old Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm. My parents and I. My very first full evening of opera. I’m nine years old.

Mom and dad have assured me that there’ll be lots for me to see—colorful costumes, entertaining special effects and surprising changes of scene. Mozart’s music is not particularly difficult.

And the dialogue is spoken, so it should be easy also for children to follow the story.

But when the curtain goes up, the child-friendly performance that my parents were expecting immediately comes to naught. The stage is bare and completely dressed in black. The costumes are minimalist and colorless. Thus, a typical mid-20th century high-modernism stage production. Nothing at all for a nine-year-old to look at.

I soon am very, very bored.

The curtain goes down. Intermission. We leave our seats and walk into the golden foyer for refreshments. And entering the enormous, anything but minimalist golden foyer, I instantly forget my boredom. I am totally absorbed in the sparkling crystal chandeliers, the ladies in glittering dresses and silver shoes, and the men with their dazzlingly white shirts and ostentatious cuff links. For the first time, I get an insight into what the grown-ups really get up to when they organize baby sitters, dress up, and venture out into the night without their children. Wow,

I think to myself, not only kids like to play. This is what grown-ups do when they play together!

It’s the first time that I really feel invited into the world of grown-ups, and almost grown-up myself.

All through the 20th century, the society into which I was born insisted on branding itself the most modern, egalitarian, and progressive society in Europe. And us kids all learned to take pride in this progressiveness too, of course. Yet, the experience of a totally anachronistic 19th century bourgeoisie time warp, carefully hidden away inside a forgotten bourgeoisie pocket of modernist Swedish society, and restricted only to intermissions at the opera, still is one of my most pleasant childhood memories. Because in the midst of all that golden foyer bling-bling—in spite of the egalitarian zeitgeist, in spite of my tender age, in spite of my lack of education in the field of classical music, in spite of my lack of opera experience—I did not feel excluded or discriminated against. And because the restless nine-year-old kid who had hoped to watch something visually extravagant and spectacular on stage, but instead had to endure 20th-century-Mozart-for-cerebral-minimalist-ascetics-only, did feel discriminated against.

To this nine-year old, on that particular night, the supposed egalitarian

20th century culture reared its ugly, patronizing, élitist head.

The theaters of 19th century typically have (a) a horseshoe-shaped auditorium, and (b) a special intermission foyer. The auditorium and the intermission foyer are of the same architectural dignity and are as lavishly decorated—because mingling with the other members of the audience is as important an ingredient of the total experience as the performance on stage. In the 19th century, the house lights are not dimmed during the performance, and members of the audience can exchange glances and flirt with one another during the performance. The boxes of the horseshoe-shaped auditorium provide the privacy of nooks and recesses where people can devote their attention to activities other than the performance on stage (i.e. fool around). Art submissively accepts being no more than a part of this complex happening.

Subsequently, attitudes in the 19th century to art and architecture are characterized by (a) the submissiveness and relative lack of freedom of art and the artist, and (b), the complete freedom of the culture consumers to help themselves to what they want in art or to discard it, to search out or ignore, to enjoy it or to heckle it. The submissive artist gets his reward and pay-off in the universality of his art. Art in the 19th century alienates no one. Art in the 19th century can be experienced

by everyone.

The theaters of the 20th century, on the other hand, are characterized by (a) the absence of a horseshoe-shaped auditorium, and (b) the absence of a special intermission foyer, which means that 20th century theaters lack a natural spatial focus for traditional foyer mingling. In the 20th century, the intermission has been reduced to a break to take a leak, and to a necessary evil endured in more or less dreary surroundings. The performance is indisputably more important than the intermission. Art is indisputably more important than life. When the curtain goes up, the lights are dimmed in the auditorium, and people can no longer flirt with one another during the performance. In the 20th century, a visit to the theater has been reduced to theater only,

and nothing else.

Thus, attitudes in the 20th century to art and architecture are characterized by (a) the total freedom of the artist with regard to his artistic expression, and (b) the new, enforced submissiveness and relative lack of freedom of the culture consumer. The artist is punished—by the loss of art’s universality—for having rejected all authorities. From now on, art alienates the majority; not everyone understands

it anymore.

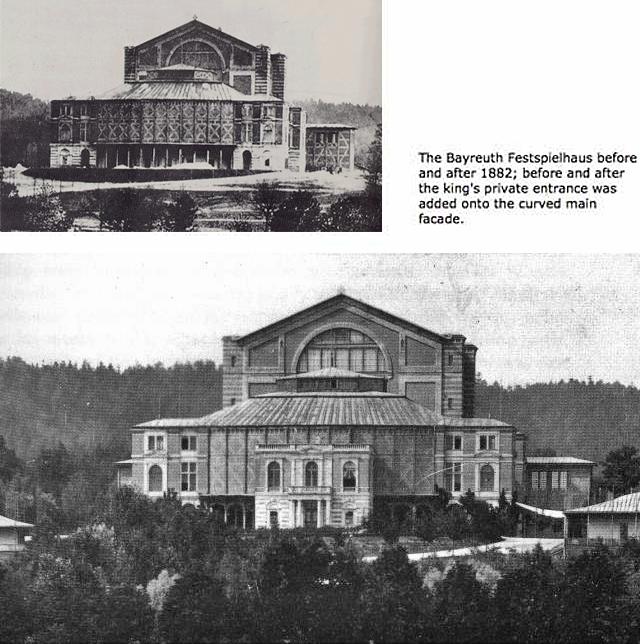

The model for all 20th century theaters is, without a doubt, Richard Wagner’s Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (designed by opera composer Richard Wagner together with architect Otto Bruckwald). Wagner is the one who introduces the practice of dimming the house lights when the curtain goes up. He does away with the traditional intermission foyer, because he feels that the members of his festival audience should devote themselves to art instead of mingling and socializing.

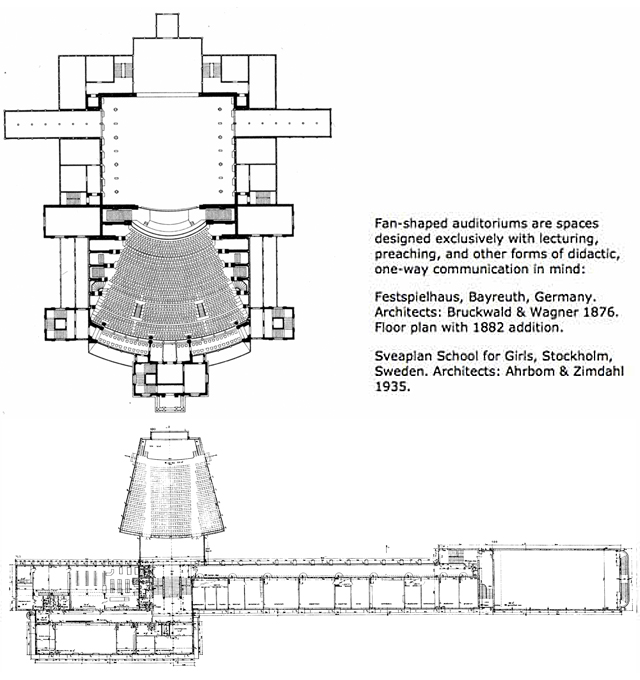

The auditorium is fan-shaped. The horseshoe shape of olden days is considered undemocratic,

since many of the seats afford only a poor view of the stage. The fan-shape is intended to democratize

the theater by giving the same excellent view to everyone in the audience.

In actual fact, though, the altruism

of Wagner’s democratic,

darkened auditorium is a disguise. There is nothing humble about Wagner’s demand for the audience to submissively give its undivided attention to his art, and nothing else—just like the pupils in a classroom or lecture hall are expected to submissively devote their full attention to the teacher or lecturer, without causing any disturbance.

So, as far as Wagner is concerned, art is obviously something to be taught

—a notion that all subsequent modernists come to share. And, didactic art (art that teaches

) demands quite a different kind of architecture to art that is satisfied with being experienced.

Structurally, conceptually and organization-wise, the theaters of the 20th century (all taking their cue from Richard Wagner) have, therefore, much more in common with the school buildings of the 20th century than with the theaters of earlier periods.

The theater architects of the 20th century make use of the spatial solutions and logistics of schools and institutions of higher learning. The theater auditoriums increasingly come to resemble lecture halls or classrooms in which art is taught

to an audience that submits to a lesson

entirely on the terms of the architecture and the performance. The intermission foyer has gone. The pupils

have to content themselves with taking a break

during the intermission in the prosaic cloakrooms and stairwells that primarily serve the same mainly logistic purpose as school corridors.

With the arrival of modernism, art loses its universality. It can no longer just be experienced,

it can only be understood,

and in order for an audience to acquire the necessary understanding,

art needs to be taught.

Modernism, in all its manifestations, is always of a didactic, teaching

nature.

The utilitarian and democratic

design of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, inaugurated in 1876, would prove remarkably prophetic with time; in particular its supposedly very democratic

fan-shaped auditorium.

However, a few years after its inauguration, in 1882, the king (Wagner’s sponsor) de-democratized

the building somewhat, by adding his very own private entrance and monumental staircase (protruding at lower center of the floor plan, above), thereby hiding from view to this day the modernity of the original exterior’s curved windowless auditorium wall.

But in spite of the 1882 de-democratizing,

monarchist addition—for architects, the mass-education

pretention of Bayreuth still sets the agenda. For instance, take the new opera house in Gothenburg (Göteborg), Sweden: the untrained eye might be fooled by the kitsch and busy untidiness of its facades (architects: Lund & Valentin 1994). But behind the populist rhetoric and popular appeal of the exterior, reigns the typical disdain and contempt of high-modern art for non-art: the opera house auditorium as lecture hall,

the foyer as school corridor.

Rhetorical kitsch architecture masks the fact that the architect actually still clings to traditional modernistic concepts and categories (which he, deep down, cannot or does not want to give up). Architecture is still a truly modernistic practice at heart. As far as the field of architecture goes, the rumors of the death of modernity have been greatly exaggerated.

This stubborn reluctance against questioning the virtues of modernist conceptualization would of course cause no problem’s for today’s architects, were it not for the fact that, outside the field of architecture, the rest of the world has probed and deconstructed 20th century modernity for decades. The rest of the world has moved on.

As we are entering the 21st century, architects were never more frustrated or unhappy. The art of building is in bad shape, they say. Architects feel mistreated by builders and politicians. And they feel misunderstood by the general public. In an article in Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet (December 3, 2003), Claes Britton and Thomas Sandell describe how they think this crisis should be dealt with, namely with education in town planning and architecture, in schools, for the general public and, especially, for our politicians, businessmen and other decision-makers.

The suggestion is scarcely original. We’ve heard it all before: If only all the non-architects knew more about architecture, we who are architects would be appreciated in the way we deserve.

Thus speaks someone who is more concerned with the social standing of architects than the future of architecture, one would think. And, what’s worse, the suggestion is impracticable. How is this mass education of laymen, decision-makers and politicians to be carried out in concrete terms? Evening classes? TV advertising campaigns? Besides, who’s to foot the bill? And how can one be sure that spending all that money will be worth while? Sweden’s Architecture Year 2001 was a very ambitious, state-supported, nation-wide mass education venture—but it did not manage to change the standing or professional role of Swedish architects. Neither did Svenska hus, the lavish 1995 TV series about Swedish architecture, make any deeper impression.

And is it really true that more architectural education for laymen automatically will generate better architecture? After all, there is no evidence anywhere of a direct relation of cause and effect between, on the one hand, the architectural knowledge of the public at large and, on the other, the quality of architects’ designs. The general public has never had more widespread architectural knowledge than today. Not long ago, the common man didn’t read or write, and was of course totally ignorant about the arts. Yet, remarkable architecture was erected. Hundreds of students are currently enrolled every year at Sweden’s three architectural colleges, compared to just a couple of students every second year or so at the single architectural college in existence a hundred years ago. Yet the art of building in this country supposedly is in worse shape today than it was fifty, a hundred-and-fifty, or even two-hundred-and-fifty years ago.

As we have seen, the cry for mass education obviously serves no rational purpose in the real world. Yet, today’s architects choose to shut their eyes to the intellectually dishonest, as well as to the impracticable aspects of the project. All out of nostalgia, of course:

The exhilarating example of Wagner and Bayreuth taught artists (and architects) all over the world to reject tradition and authority, and to put themselves and their art first. Therefore, teaching the public this new, untraditional concept of art became essential. Art and architecture became didactic, educational;

e.g. as we have seen in the case of modernist theater design, architects and performers cooperated in banning the complex multi-directional social interaction between stage and audience (and, not least audience-to-audience) enhanced by traditional (oval) auditorium layouts, instead turning theaters and auditoriums into machines of one-way-information, fan-shaped lecture halls

for lecturing and teaching the public greater respect for the genius of the performer.

And for almost a century, the artist/architect had his way. The public responded well to this indoctrination. Artistic genius was truly worshipped.

But with the recent (late 20th century) collapse of modernist utopia, and the ensuing mistrust in modernist values, the days of cultural heroism and of hero architects are gone. The artist/architect no longer is recognized as the closest thing to God. Truth

in architecture has been replaced by arbitrary taste.

The architect can no longer expect the general public, politicians or building contractors to immediately submit to how the architect would prefer things to be/to look. Computers, DVD-players, commercial building contractors, multinational manufacturers of kitchen appliances; they all have become much more important than architects for providing the kind of contemporary experiences and comforts which actually are in demand.

However, the architect of today refuses to acknowledge this situation. He insists on the great importance

of good

architecture, refusing to accept any relativity of architectural goodness

and truth.

All resistance to good

architecture is indeed to be mass educated away! But the world around him remains unimpressed. Even Sweden’s government-sponsored Year of Architecture 2001 achieved—absolutely nothing. Confused and puzzled by the world’s disinterest, today’s frustrated architect turns to the wishful thinking of the mass education project, because the mass education project offers today’s frustrated architect the comfort and consolation in entertaining disproportionate and obscene fantasies of future world domination, i.e. obscene fantasies of global submission to the architect.

Appendix

An exception to the rule of Wagnerian hegemony: the floor plan of the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm (the nation’s capital and first city), with its pompous neo-baroque (oval) auditorium and its golden foyer, was old fashioned

/unfashionable already before the opera house was inaugurated (i.e. the building’s floor plan and layout shows no influences from Bayreuth). Architect: Axel Anderberg 1898.

www.futurdesigndays.com

www.futurelab.se

Thinking Out Loud #1 (Ljudbok på svenska och engelska)

Thinking Out Loud #1 (Audio Book in Swedish and English)

Häpp!

More by Mikael Askergren about the architecture of theaters:

Vem älskar finkulturen?

Betongturism

Villa Spies

Illustrations

• Old photographs of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus before and after the king’s private entrance was added onto the curved main facade (in 1882).

• Festspielhaus, Bayreuth, Germany. Floor plan with 1882 addition (the king’s private entrance). Architects: Bruckwald & Wagner (1876).

• Sveaplan School for Girls, Stockholm, Sweden. Floor plan. Architects: Ahrbom & Zimdahl (1935).

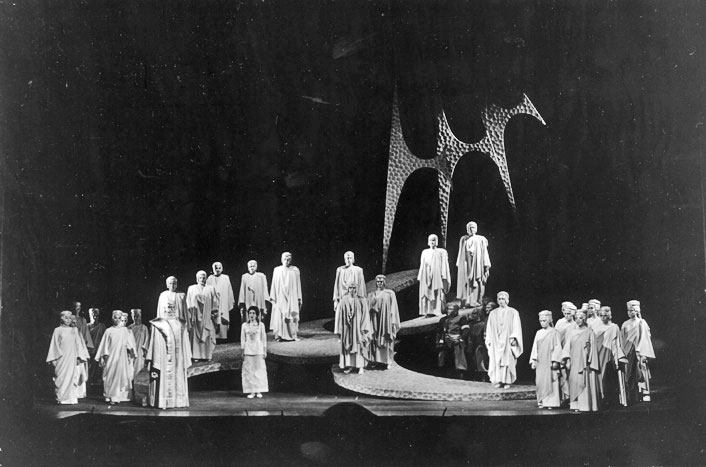

• Video. Furtwangler (or Abendroth?) in Bayreuth 1943. YouTube.